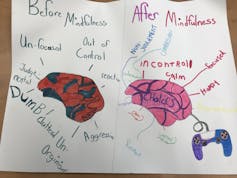

How do girls feel before and after learning mindfulness? The six girls in our program, aged 11 and 12, drew pictures showing that learning and practising mindfulness helped them feel more in control and compassionate, less judgmental, happy, focused, calm and logical, especially when they make good choices.

These girls had just completed the 12-week holistic arts-based program (HAP) that we offer at Laurentian University, which teaches mindfulness-based practices and concepts using arts like painting, drawing and collage, or materials like clay and sand. We also incorporate games and and tai chi.

I developed HAP with the help of Hoi Cheu, a professor in the English department with training in film making, marital and family therapy, tai chi and mindfulness. Part of our early team were Sean Lougheed (with a graduate degree in child and youth care), Jennifer Posteraro (research co-ordinator with a graduate degree in psychology) and Julie LeBreton (social work student).

Youth facing challenges

We wanted to respond to the needs of marginalized children in our communities — such as those who face diverse challenges, including academic, mental health and social challenges, and those facing life circumstances such as abuse, bullying, social exclusion, poverty or family dysfunction.

We wanted to help them build skills and capacities such as paying attention, and for improving peer relationships and mood. But we knew that these children may not have the attention skills required for a more traditional mindfulness program.

In developing the program, we drew on the extensive knowledge bases of art therapy and arts methods with youth. We then refined the program through research with children involved with the child welfare and/or mental health systems.

We receive referrals for the program from a variety of sources, including mental health practitioners, guidance counsellors, principals and teachers, child welfare workers and self-referrals (mostly from parents).

Self-compassion, acceptance

Discussions about mindfulness seem to be everywhere these days, including some schools. Mindfulness has come under criticism as it has gained in popularity throughout the West. Some say institutions that use it may encourage or distract people from advocating for systemic change. We understand that systems need to be challenged and changed. In our program, we work to assist individuals and groups to cope better with, and challenge, the oppressive or unjust systems in their lives.

Since 2009, more than 300 other youth from our community have participated in our arts and mindfulness program. Over a two-hour period, two facilitators lead small groups of participants. Through the activities they aim to help participants work together, learn about themselves and express their feelings and thoughts and practise breathing, self-compassion and acceptance.

The drawing by several girls in the program of a brain before and after mindfulness is a wonderful depiction of the benefits of learning mindfulness, often defined as the ability to pay attention, purposefully, to the present moment without negative judgements. The power of mindfulness is the ability to make choices about one’s feelings, thoughts and behaviours rather than reacting and acting out.

‘Happy awareness program’

Creative activities such as painting how music makes you feel or drawing yourself as a tree aid in identifying and naming feelings, communicating these feelings and thoughts and discovering things about yourself in ways that are effective and developmentally relevant. Belonging to a supportive group helps youth develop a wide variety of capacities and strengths such as social skills, empathy and self-awareness.

Common reported benefits of mindfulness-based interventions with youth often include improved emotion regulation, mood and well-being and decreases in stress and feelings of anxiety. Almost all of the youth we have worked with described the holistic arts-based program as “fun.” One youth suggested we re-name our program the “Happy Awareness Program.”

Benefits to mental health

In our research with youth admitted to a small in-patient mental health program, we found that youth who participated in the program activities reported that the program was enjoyable and beneficial in that they learned to identify and express what they were feeling, and they could focus better and think in different ways.

We interviewed the youth and they shared feedback about their experiences:

“I learned that I like doing art and it relaxes me and makes me express myself better.”

“Being mindful helps with the anxiety that I have and helps me just focus either on my work or something else that I am doing.”

“There are a lot of fun activities that can help you find yourself and find peace within yourself, to relax and catch your thoughts instead of them jumping all over.”

There are a multitude of mindfulness-based programs for youth, many of which have been adapted from two well-known programs originally developed for adults: mindfulness-based stress reduction, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Two examples of programs for youth developed by clinical psychologists are Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children and Learning to Breathe.

Strengths-based change

Arts-based activities do not have to be complicated. For example, having group members notice and write down each other’s strengths can begin to shift the negative beliefs youth have about themselves. Developing self-compassion and self-acceptance is an important part of living more mindfully and experiencing well-being.

Awareness and expression of feelings can be facilitated by drawing what we call feelings inventories. Such feelings inventories are always unique.

Based on our research experiences, we have become strong advocates of teaching mindfulness-based practices and concepts through the arts.

Through this approach, we can make the cumulative benefits of practising mindfulness more accessible to diverse groups of youth — and youth are enabled to express themselves in relevant, meaningful and developmentally appropriate ways.

I have learned through my work that change does not have to be daunting. Important learning can take place through experiences of fun and belonging.

Diana Coholic, Professor, School of Social Work., Laurentian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.