This article, written by Michael J. Armstrong, Brock University, originally appeared on The Conversation and is republished here with permission:

The anniversary of Canada’s recreational cannabis legalization arrives Oct. 17, just days before the federal election. Legalization was a Liberal campaign promise from the last election, so it’s timely to review how it’s worked out.

Consumers evidently like legalization. Statistics Canada just reported that July’s recreational sales hit $104 million.

Politicians apparently like it too. It’s an election promise the Liberals kept and that no other party plans to repeal.

But how well has it reduced black market cannabis, as promised?

Increasing legal sales

A government-funded study in 2018 estimated Canada’s total cannabis consumption at roughly 926,000 kilograms annually, or some 77,000 kilograms monthly.

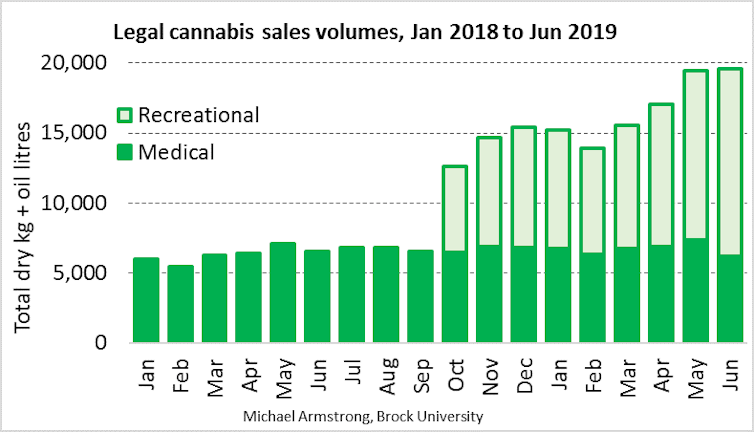

Health Canada says that in June 2018, when only medical usage was legal, licensed producers sold 2,151 kilograms of dry cannabis and 4,652 litres of cannabis oil. That represents around nine per cent of national demand.

In June 2019, by comparison, legal medical and recreational sales totalled 9,976 kilograms of dry and 9,614 litres of oil. That’s about 26 per cent of the market.

So legal sales have roughly tripled. But illegal sales remain the majority.

By contrast, StatCan seems more optimistic. Its surveys ask users whether they buy at least some cannabis legally. It estimated that number at 47 per cent, or 2.5 million Canadians, for the first quarter of 2019. That’s up sharply from 23 per cent, or 954,000 people, in 2018’s first quarter.

Unfortunately, those estimates aren’t really plausible. The only people who could legally buy cannabis in March 2018 were Health Canada’s 296,702 registered patients. And just 132,975 did so. That implies StatCan’s estimates are three to seven times too high.

So while survey participants reported purchasing legally, they mostly didn’t.

Growing pains

One reason legal sales haven’t done better is a lack of retailers in some regions. British Columbia and Ontario were especially slow to open stores.

Product shortages have posed bigger problems. While there’s ample oil, producers until recently hadn’t processed enough dry products. And legal foods, drinks, vapes and lotions aren’t yet available.

Those shortages are predictable side effects of the government’s legalization strategy. It chose a regulated pharmaceutical approach, rather than the more hands-off approach many U.S. states have used.

That hands-off approach has several drawbacks, however. Ex-black-market producers don’t always prioritize consumer safety. Some reportedly fudge their product lab tests.

Furthermore, minimal government oversight is worrisome to social conservatives. Almost 80 per cent of California cities banned state-licensed cannabis shops.

But the pharmaceutical approach has its own drawbacks. Rigorous standards prevent existing grow-ops from going legit. Instead, they remain illegal and undercut legal producers’ prices.

Meanwhile, legal producers need time to build facilities and gain experience. That almost guarantees initial product shortages.

It’s understandable the feds chose the regulation-heavy approach. But as I and others have complained, they shouldn’t be denying its limitations.

Head-spinning spin

Already in January, Border Security Minister Bill Blair was implausibly bragging that cannabis supplies were “adequate” and “exceed existing demand.”

That was despite government data showing legal production met less than a fifth of Canada’s dry cannabis needs that month.

A Newfoundland store even closed due to the shortages.

In March, Health Canada spokespeople similarly said “there is not — as some have suggested — a national shortage.” That was when shortages were keeping Québec’s shops closed three days a week and preventing hundreds of Alberta store openings.

Those premature claims only added to the frustrations felt by retailers and consumers.

However, some other criticisms of the government seem frivolous.

Other complaints

For example, some critics say the government legalized too slowly. Edibles should have been allowed sooner to better compete with black markets, they say.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t realistic. Given limited regulatory resources, it made sense to legalize simpler dry and oil products first. That allowed another year to figure out the rest.

Besides, producers have struggled to supply just two product categories. More categories would have meant more severe shortages.

Conversely, other observers argue legalization went too quickly. They think governments should have resolved problems like product shortfalls and impaired driving before beginning sales.

Again, that’s unrealistic. First, legalization has been discussed since 1972’s Le Dain Report; 46 years isn’t rushing.

Second, the government only has four years between elections. Had it moved more slowly, legalization wouldn’t have happened.

Finally, many problems require research to resolve. Since legalization, Health Canada has issued 145 research licences and hundreds more are pending. Studies have already examined grow-op lights, black market financing and alternative retailing strategies.

Canadian compromises

Canada has come a long way since 2001, when the government began the process of legalizing medical cannabis. In a sense, we’re 15 years ahead of Australia and 17 ahead of Britain.

Here, recreational users now grumble about product quality and wasteful packaging. But in the U.K., epileptic children still struggle to access medical cannabis oil.

Yes, legalization has been a muddled mess of compromises and glitches. It still needs years of work. But at least it happened. And it’s taken a bite out of black markets. So it should be considered a typical Canadian success story.

Michael J. Armstrong, Associate professor of operations research, Goodman School of Business, Brock University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.