As a new spring semester begins in Canada, all-online teaching continues. In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, universities and colleges replaced classroom instruction with online teaching. UNESCO estimates that more than 1.5 billion students in 165 countries are affected by a move to online learning.

With campus libraries still closed, instructors have had to place more course materials online.

Canadian educational institutions have long been concerned about the risk of being sued for copyright infringement. For example, how instructors or libraries permit materials to be copied and shared, or how materials are shared and credited, can all come under scrutiny.

Universities and colleges have adopted copyright guidelines, and they provide trained copyright specialists to help faculty and students navigate these issues.

But the abrupt shift to online teaching creates new copyright issues for institutions and educators.

Everything online is recorded

Online course management systems (CMS) record all entries into their systems. All teaching activities can be audited by the institution or at the request of a third party (like a publisher).

When an instructor uploads a new resource online, they must first certify its copyright status before posting.

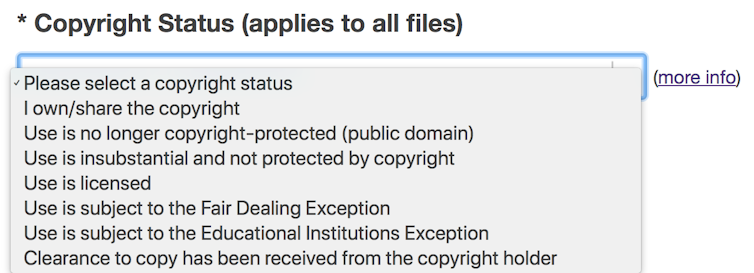

For example, here is a sample prompt that instructors see on Western University’s in-house online learning platform. It asks instructors to identify the document’s copyright status:

As people with considerable experience with Canadian copyright law in the educational sector, we believe that universities and university instructors can assume that the circumstances of the current emergency justify a broad application of what’s called “fair dealing.”

A flexible user’s right

Fair dealing is a flexible users’ right that allows the reproduction of copyright-restricted materials without the permission of, or payment to, the copyright owner in certain circumstances.

Copyright law gives owners broad exclusive rights and powers to restrict the use of their intellectual property without permission. At the same time, the law also gives the public rights to use copyright-restricted resources without risking copyright infringement.

In Canada, the most important of these rights is fair dealing. The purpose of fair dealing is to balance the rights of owners and the public interest.

Applying fair dealing in Canada

Determining if something can be considered fair dealing involves analyzing two factors. The first is whether the use falls within one of the categories listed in Section 29 of the Canadian Copyright Act, which states:

“Fair dealing for the purpose of research, private study, education, parody or satire does not infringe copyright.”

Since “education” was added as a listed category in 2012, the first part of the test is not an issue.

The second part looks to whether the particular dealing by a user is fair. The Copyright Act does not list the criteria, but a set of six fairness factors was adopted by the Supreme Court of Canada in the landmark case of CCH vs. Law Society of Upper Canada (2004).

Let’s look at the fairness factors

-

Purpose of the dealing: The Supreme Court of Canada decision said the purpose of the dealing is a factor that should be considered. Enhancing education for students online is a strong purpose. The current extraordinary circumstances of the current pandemic make the public interest goals in maintaining access to educational resources indisputable.

-

Character of the dealing means how the works are being used. Using online resources to support ongoing course work strongly favours fair dealing.

-

Amount of the dealing: The quantity of copying helps determine fairness, but it’s not a mechanical application. This factor favours fair dealing where the amount being copied is necessary to further the purpose of the dealing.

-

Alternatives to the dealing means whether there is a non-copyrighted equivalent of the work that could be used instead of the copyrighted work. Given the coronavirus context and how fast instructors have had to go online, it’s likely that most materials they put online are core materials. It wouldn’t be reasonable to expect students to purchase additional materials in an emergency. The Supreme Court has ruled that the availability of a licence is not relevant to evaluating fair dealing.

-

Effect of the dealing on the work: The public interest in using the work must be balanced against any harm to the copyright owner. In its 2012 decision in Alberta (Education) vs. Access Copyright, the Supreme Court clarified that the owner must show demonstrable harm in order to turn this factor against a fair-dealing claimant. That harm must be related to the actual use. Making generalizations about lost sales due to copying won’t suffice.

-

Nature of the work: This factor considers the impact of whether the work was published or unpublished, confidential or non-confidential. It’s unlikely to apply to course materials that have already been published.

U.S. and Canadian contexts

In the past two decades, Canadian courts have interpreted fair dealing in broader terms. These interpretations have meant that Canada and the U.S. have come to take very similar approaches to fair dealing (or what the U.S. calls fair use).

A group of U.S. copyright experts issued a Public Statement of Library Copyright Specialists pertaining to universities’ use of materials during the coronavirus crisis. They conclude that:

“…making materials available and accessible to students in this time of crisis will almost always be a fair use … fair use … accommodates the flexibility required by our shared public health crisis.”

We believe this conclusion is also valid in Canada. We are confident that a very broad application of fair dealing is justified under the current circumstances.

We encourage everyone posting online course materials to make full use of the flexibility the law allows to maintain and enhance student learning.

The authors thank Marie Blosh (J.D., M.L.I.S) for her helpful comments and editorial assistance.![]()

Samuel E. Trosow, Associate Professor, University of Western Ontario, Faculty of Law and Faculty of Information & Media Studies, Western University and Lisa Macklem, PhD Candidate, Law, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.