Maps give us direction. I bought a map in 1993 and left it in the cardboard mailing tube with full intentions to mount it because it is a map like no other. It is not a folded map from the glove compartment.

A thematic map focuses on the spatial variability of a specific distribution whereas a reference map focuses on the location and names of features. When you look at maps, particularly topographic, most of the indigenous names have disappeared. That is because the settlers prefer to name natural features after people like politicians, surveyors and loved ones.

One map though is both a reference and thematic map; it is different and almost thirty years later it remains revered by many as a pathway to understanding. It is a large map 96 cm x 139 cm (38”x 55”) with heritage graphics covering a wilderness area well over 10,000 square kilometres north of North Bay, east, straddling the Ontario/Quebec border, west to Lake Wanapitei and north towards Elk Lake; Lake Temagami is in the centre.

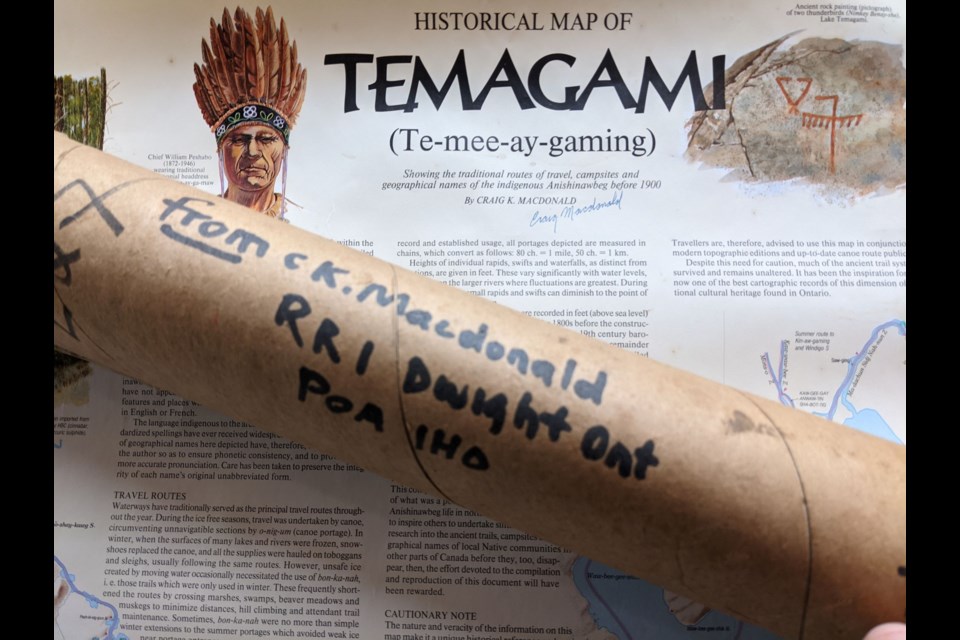

Craig Macdonald’s creation is called the Historical Map of Temagami and it presents a unique and invaluable contribution to our understanding of the aboriginal world that existed in Canada prior to contact with the colonialists. Because I have taken my tightly rolled map out of the cardboard mailing tube I had to contact him; it was time to plot a course.

The map includes the names of 660 features – lakes, rivers, creeks, islands and highlands – all in the language of the Anishinawbeg. It depicts traditional winter and summer travel routes and identifies hundreds of portages, along with their exact lengths.

Craig Macdonald is an ethno-geographer, Cree-Ojibwa place-name linguist and trails expert who spent 27 years doing research in the area. He interviewed more than200 Anishinabai elders and travelled over 1,000 miles in the backcountry exploring the nastawgan and methods of travel on them. Craig estimates the nastawgan have been in use for over a thousand years. From his painstaking research and devotion to native-travel methods and routes, the word “nastawgan” has moved from the aboriginal language into the language of the modern canoeist.

How did this journey start? “At the time (1966) I was canoe trip guiding for Kirk Wipper at Minis Kitigan on Mons-kaw-naw-ning. Our access was Mowat’s Landing where Peter Albany and his family lived in two wall tents. It was here that I got to know him.” It was a point when he would become a knowledge keeper.

The map was first published 1988 as he says with "… no errors, no updates or changes, however, the spelling of some of the names could be improved for more accurate pronunciation, I am still selling the original first printing of the map."

The map was first distributed to Temagami band elders. In many cases, the elders had already died so copies of the map were given to their descendants. Maps also went to others who helped with the project.

He regrets that the project was not started in 1965 before Chief Alec Paul died. The linguistic information for the west side of the map would have been greatly expanded by Alec.

He worked 47 years for Lands and Forests and Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario.

“Most of my life has been spent working in the woods. I have travelled widely in the north, from Point Barrow Alaska to Nain Labrador. I have spent a lot of time both in canoes and on snowshoes on extended voyages lasting weeks.”

This map is the first truly detailed look at the native travel landscape for anywhere in North America. It depicts the Nastawgan or waterway travel routes for Temagami.

“Contrary to what many people think, nastawgan are more than just canoe routes because they include the special snowshoe trails called bon-ka-nah that were necessary for winter travel on waterways. These trails are depicted on the map as green lines and were only used during winter. They avoid weak ice in lake narrows and unsafe river ice. They also provide winter short-cuts to the routes travelled during the summer by often traversing swamps and muskegs.”

One of his favourite Temagami destinations is what we know as Maple Mountain.

“On a clear day, Chee-bay-jing has the most spectacular long view of the surrounding landscape of any place in Northeastern Ontario including Ishpudina ( the highest point in Ontario). The mountain is a very sacred place for native people,” he says.

New book coming

Then I discovered there’s going to be a book on the map, giving us more direction. In 2020, James Raffin was named by Canadian Geographic as one of the “90 most influential explorers in the nation’s recorded history.”

He is the author of many natural and cultural heritage books. One of my favourites is Deep Waters: Courage, Character and the Lake Timiskaming Canoeing Tragedy as I utilize this risk-related story in my outdoor education classes at Nipissing University. He is now writing about Craig’s map.

What it represents as time moves on for the people of Bear Island, and how it came to be. It’s a project sponsored by the Temagami Community Foundation (TCF) in cooperation with Teme-Augama First Nation and the Teme-Augama Anishinabai.

It will likely be published by Dundurn Press in the spring of 2023 if all goes according to plan. I’ve been researching the book for about a year and a half now and am just moving into the writing phase over this winter, hoping to have a publishable draft by next spring.

The intent of the book is to highlight what is a truly remarkable body of work by an equally remarkable man.

If you got the map 30 years ago, then you’re likely at least a little bit familiar with Craig and his passions.

Crazy that a guy with an MSc from the University of California (studying the life cycle of an obscure type of fish) who worked as a recreational specialist for the Ministry of Natural Resources, working on trails in Algonquin Park, would end up creating a unique ethnographic map and a detailed manuscript about winter trail and travel technology in northern Ontario.

He had no training in ethnology nor in cartography and yet, in his spare time, Craig interviewed scores of elders and others and collated the information that allowed him to create the Historical Map of Temagami and an as yet unpublished treatise on traditional winter travel techniques that is to sleds, toboggans and snowshoes what Edwin Tappan Adney’s 'The Bark and Skin Boats of North America' is to the birch bark canoe.

I can think of no one else with this kind of range of interests or dedication to what was a semi-impossible thankless task.

'Mr. Macdonald’s Map' was the working title but, with the noise now that the name Macdonald conjures in the public mind, the book will be published with a less incendiary and more evocative title. We’ve got lots of ideas but nothing is firm yet.

I undertook this project because of friends Dick and Victoria Grant at the TCF asked if I might consider writing the book for the foundation, and as a writer and independent scholar, I’ve been drawn to cross-cultural spaces for most of my adult life.

I’ve known Craig Macdonald since I was five years old, as a youngster at Camp Kandalore, and I’ve travelled with him, over the years, on many of his research trips in Quebec, Northern Ontario and beyond.

I also think the work he has done was a form of reconciliation long before reconciliation was a “thing.” And it’s a great tale of passion, intrigue, trust, dedication and how a white guy from North Toronto won the hearts and minds of indigenous elders from Nunatsiavut to the Beaufort Sea, particularly those in mid-north Ontario, and how those elders provided Craig with information that might otherwise have been lost within an oral culture and tradition in changing times.

Different Craig perspectives

Maps are open to interpretation and it takes some skills to read the terrain.

If you mention the name Hap Wilson you immediately think of canoeing and the Temagami wilderness. As well, he has written canoe route books highlighting this region. He was contacted and he explained some of the past histories of the area.

Craig’s directive was in the preservation and location of aboriginal place names; my directive was to define, consolidate and preserve the nastawgan, or canoe routes from the encroachment of logging, and to 'spread-out’ the user-traffic (the only park in Temagami at the time was the Lady Evelyn River Waterway Park which was getting over-used).

Before I knew Craig I had already defined the Temagami canoe backcountry which coincidentally mirrored N'daki Menan - the traditional territory of the Teme Augama Anishnabeg.

Logging companies had carte blanche access to rich timberlands; roads created more access to fish and game. I worked on the initial park plans as their cartographer/researcher, as well as the MNR profile maps used during the First Nation’s court case.

After leaving the MNR and starting my outfitting company and co-founding the Temagami Wilderness Society, I remember that we pleaded with Craig to get his map released that would have helped in our battle to protect the nastawgan. Craig was a "company" man and his hands were tied - the MNR wouldn't allow the map to be released until it was to MNR benefit and not an aide to protectionism.

I have great respect for Craig, nonetheless, but I did question why the map didn't include English translations (at least on the back of the map). I had studied the Ojibwa language and knew many of the translations and knew that the place-name stories would have taken up a lot of map space, but for the average person - the aboriginal names meant little. Craig opted to keep most of this valuable information in his head; I found that the most interesting facet of the map is the way it was drawn showing the original, undammed, lakes and rivers.”

Dr. Jonathan Pitt is an Indigenous knowledge keeper and is of Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee heritage. Cultural transmission is part of his research and the courses he teaches at Nipissing University through Aki or land-as-teacher. He also works as an Independent Consultant for post-secondary organizations as an Indigenization Advisor.

In my mind, the map serves as a historical record, as Macdonald interviewed many Elders and Knowledge Keepers in the making of the map.

As the court systems of the Canadian colonial experiment, even to this day, do not honour Indigenous ways of knowing or knowledge systems, Macdonald’s map would have been accepted by the white man’s law. Several First Nations have contacted him and sought advice about undertaking similar mapping projects.

In the late 1980s, the Bear Island Anishinawbeg in Temagami utililized Macdonald’s testimony during a land claim hearing before the Ontario Supreme Court. His research established they had utilized the land since at least the 1600s.

In some ways, the map serves as a historical record, in other ways it also reminds us that Indigenous people have not been honoured by Canada since the advent of settlers.

It is a reminder of the colonizer and the colonized. People need to realize that times have changed and this map serves as a reminder and place to start teaching Canadians what the essentialist and standardized schoolhouse curriculum left out.

Then there is Brian Back. He co-founded the Temagami Wilderness Society in 1986 and became its executive director.

The Society opposed logging expansion in Temagami and, in the process, the group became the largest single-issue environment group in Canada. In 1990, he founded Earthroots Coalition and was executive director until his departure in 1992.

If you want to know anything about the backcountry in the Temagami, go to his site.

“Craig’s map defines the Temagami that existed prior to rail, road and settlers when the canoe was the family van and the snowshoe was the Skidoo. It brings to life to anyone looking at it that there was an ancient people living on this large expanse of land called Temagami.”

He recalls when he first met Craig.

The Sturgeon River is an old trade route used by the Nipissing First Nation, a once-great trading nation, for the return from James Bay.

I was camped at Upper Goose Falls on the Sturgeon River in 1970 when Craig came through, our first meeting. He had travelled downstream from the Montreal River and tried to get to the Sturgeon on the ancient 1.5-kilometre portage from Hamlow Lake.

The bottom half of the portage had just been clear-cut and he had a brutal scramble to get through the mess. That section of the trail was obliterated. Craig was probably the last person to cross it.

He was pretty upset at the time and that was a wake-up call that a map was needed before more was lost. With the aid of his map, I found old sections of the portage about ten years ago and restored them to use. It is now well-trodden again.

In the 1980s he had worked on it for years. It would have helped the environmental battle then and the Temagami First Nation’s land claim. But he was a perfectionist and would not take it to print.

There were still a couple of portages he had to double-check his research first. He was not going to make any mistakes with the heritage of the Temagami First Nation.

That’s the kind of guy he is. Temagami is lucky to have him. I believe there is no other place in North America where the ancient trails are comprehensively documented like this. And with the loss of elders, there probably never will be another.

Temagami Community Foundation

Maps help you figure out where you are and how to get where you want to go. The Temagami Community Foundation (TCF) promotes environmental stewardship, supports community arts and culture, honours First Nation heritage while fostering sustainable economic development. It serves the Temagami region, including permanent residents, seasonal cottagers, and the First Nation. It is helping to fund the book.

Victoria Grant, Maang Indoden, (Loon Clan), Teme-Augama Anishnabai Qway (Woman of the Deep-Water People) is a member of the Temagami First Nation and one of the co-founders of the TCF and its inaugural Chair.

She has been, “Passionate in advocating for a more robust Indigenous voice within the foundation. I think it is important to my community, to the greater community and as important to this country. But what is more important is what it will mean to our future generations.”

Vicki describes the significance of Craig’s work.

This is our history, it is about our relationship to land, it is about our family.

It is about a man (Craig) who through his life listened to our elders, it is about a man who learned our language in order to map not only current travel in summer but the winter.

He earned the trust of those he interviewed and he completed what he started. He understood that what he wanted to learn about, the information he wanted, he would have to embody the values of those he was speaking with.

Sometimes when I hear Craig speak, if I closed my eyes, it could be one of those elders speaking.

This is about the importance of building strong and healthy relationships.

It is about a man who has made himself available many times, to share with us the stories he heard from our old people. We are the beneficiaries of his kindness, his work and a book that embodies all of that will be an asset not only to our community but to all who have the opportunity to read it.

She identifies an important contemporary, educational and cultural perspective.

We are living in Canada and we are hearing lots about Truth and Reconciliation.

In order to under what Reconciliation might be, we need to understand and acknowledge that Indigenous peoples in this country were civilizations, with culture, language and a governance structure.

The making of this map embodies all of that. I am so pleased that Craig has agreed to have this story written, and James has agreed to write it, and to have the book with the map will complete the Circle.

Richard Grant is one of the Co-Chairs of the TCF, his family cottage of 44 years is located on Jumping Caribou Lake.

He said, “The map will mean a great deal to the next generation of canoeists for the Temagami wilderness area. Most are not aware of the indigenous historic network of the historic nastawgan."

Folks tend to keep maps for a long time even in the glove compartment.

Back Roads Bill has canoed throughout much of the map’s area my favourite is this area Shkim-ska-jeeshing-S (Florence Lake). It is 28 years and my map has left the mailing tube and is being wall-mounted; I am developing new bearings.

This map has given me direction to understand why we cannot continue to downplay the nature and extent of the harms of residential schools and deny obligations to redress historic and ongoing colonialism as the prerequisite for reconciliation. (If you would like to order a map, email Craig at macdonal@vianet.ca)