From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

In 1877, what started as a minor conflict between two neighbours on Manitoulin Island ended with two men dead and a father and son behind bars.

The Amer family — consisting of parents and two children — had moved to Manitoulin Island to pursue farming. George Amer had worked previously as a police constable in Owen Sound, where the Globe described him “as being a most resolute and determined officer, who would execute his warrant if by any means it could be done.”

He had made the news in 1861 due to his involvement in a murder investigation, in which he and his “assistants” dramatically arrested the suspect — the story of the arrest involved weapons, “a violent struggle,” and the accused making a desperate attempt to escape by jumping into a river.

However, despite his history with the police force, George Amer would soon find himself on the other side of the law – along with his meeker son, Laban.

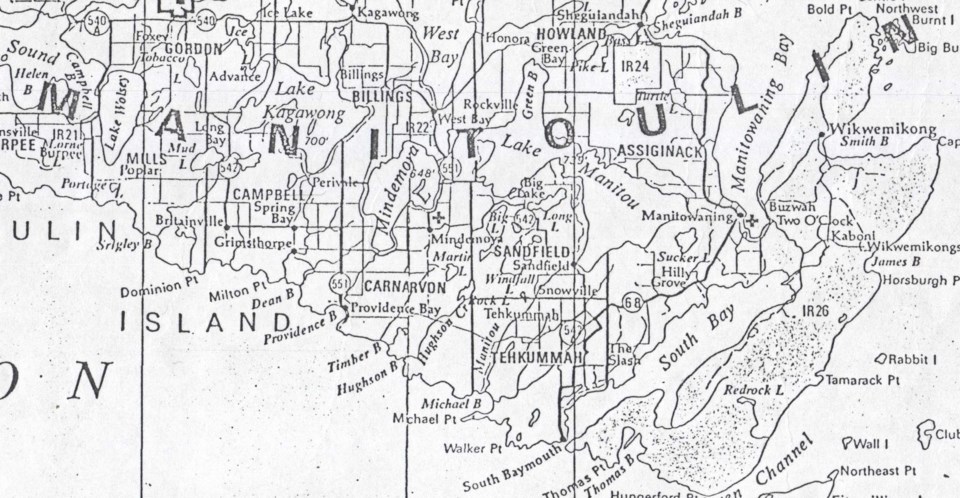

The Amer family had a farm in Tehkummah Township. The adjoining farm was owned by the Bryan family, including father William and son Charles Bryan.

The relationship between the Amers and the Bryans was not always a positive one, exacerbated by instances of their animals grazing on the other’s property. Specifically, the Globe reported that “the horses belonging to the Amers again trespassed on the Bryans’ farm, and having got into a field of wheat belonging to the latter, trampled it badly.”

Fed up, the Bryans caught the Amers’ horses, tied them up, and refused to give them back. According to a neighbour who would later reminisce about the murder in the Sault Star, the intent was that the horses not be given back until the Amer family paid for the damage done to the crops.

George Amer did not take this turn of events well. He “[armed] himself with a hickory club and a policeman’s baton” and had his son accompany him with a pistol. It was late at night by this point, and tempers flared by the time the Amers arrived at the Bryans’ farm again.

A fight broke out — father fighting father and son fighting son. The fight was so violent that neighbours were disturbed by the sound of blows landing. According to the Globe, “Amer called out to his son to shoot their opponents. The young man but too faithfully obeyed the commands.”

Laban Amer shot father William Bryan first in the neck, and then son Charles Bryan in the forehead. Badly beaten and now suffering gunshot wounds, both died long, slow deaths.

George and Laban Amer were arrested, put in jail, and stood trial in Sault Ste. Marie; Laban had initially tried to flee, but reward notices were quickly posted for his capture – including some in Sault Ste. Marie – and he gave himself up to the police.

To help investigate the case, Mr. J. W. Murray, government detective, was brought in to assist. Murray wrote of the murder in his humbly-titled, somewhat fabricated book “Memoirs of a Great Detective.” His recollection of the events focused mainly on the presence of a young girl from a neighbouring family who “was weak in her mind, and was given to spells of blackness, like the long, long nights a little farther north.”

Upon viewing the murder scene, apparently she could only speak the name “Amer” over and over, in various tones of voice. Murray was apparently quite struck with the image. He closed his chapter on the incident saying, “And ‘tis so I see her still, doddering in the doorway.”

He used this repeated name as a clue in his detective work — along with a post-mortem that had to be repeated due to the coroner initially cutting his hand, developing blood poisoning and providing an unsatisfactory report. Ultimately, Murray pieced together what he described as “wholly and purely a case of circumstantial evidence, but the chain of circumstances was so complete as to be absolutely convincing.”

The Amers stood trial for the murder of the Bryans. According to the Globe, in the case of the younger Bryan, whom Laban shot in the head, Laban was discharged and his father was found guilty of manslaughter. In the case of the older Bryan, whom Laban shot in the neck, both were found guilty of murder, a capital offence.

The defense lawyer quickly argued that, according to reminiscences in the Sault Star, “this court of Algoma was not competent to give such a judgment as that. It was too immature, too primitive, to circumscribed in its authority to hang a man until he was dead, let alone hang two men.”

The case went to the Supreme Court of Canada, where the appeal was ultimately denied. George and Laban Amer were sentenced to hang.

Meanwhile, Annie Amer — George’s wife and Laban’s mother — quickly sprang into action, organizing petitions and spearheading a campaign for clemency. George and Laban had their death sentences commuted: instead of hanging, they were to spend ten years in the Kingston Penitentiary.

They would not even serve the full ten years. Laban was released after three years due to health concerns and lived with his mother. George was imprisoned for longer but still did not serve his entire sentence before being released.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here