From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

In 1947, protests rocked Canada from coast to coast. The Second World War had ended, but the Red Scare of the 1950s was gearing up and tensions were high. People were threatened with being tarred and feathered. Others levelled accusations of communism and foreign interference, of influence and manipulation by “the Reds.”

The source of the conflict? The humble chocolate bar.

Before the war, the standard price of a chocolate bar was five cents. During wartime, the price increased to six cents, and then again in April 1947 to eight cents. This latter increase stemmed from the removal of price controls; a move that saw food prices jump nationwide.

According to a national poll, while children were still interested in buying chocolate bars, it was the “more money-conscious dad” who was “beginning to emit loud squawks of protest.” Politicians, too, spoke out against this price increase, with Co-operative Commonwealth Federation leader James Coldwell taking to the floor of the House of Commons to advocate for a return to the pre-war price of five cents.

However, it wasn’t only adults who were upset about more expensive candy.

By the end of April, news emerged from British Columbia of teenagers boycotting the purchase of chocolate bars, with hundreds of them picketing in front of candy stores. The protest soon snowballed and spread from coast to coast. Teens stormed the legislature in Victoria, B.C.; and in Ottawa, they marched on Parliament Hill; in Toronto, they carried placards and placed leaflets on parked automobiles; in Montreal, they drove up peanut sales as a cheaper snack alternative; in Halifax, youth signed petitions in droves. And across the country, chocolate bar sales plummeted, by as much as 90 per cent in some areas.

As the Sault Daily Star noted in May, “Chocolate bar wrappers tossed on the lawn are annoying at any time, but now they’re likely to bring ‘scab’ accusations.”

In Hawk Junction, a group described in the Sault Daily Star as the “’We Won’t Buy Eight Cent Candy Bars’ Union” picketed, using their bicycles to block the road. They wore signs that read, “We want five-cent chocolate bars” and “I’m no sucker.” One member of the group told a reporter that their allowance wouldn’t cover the increased cost, adding, “Down with eight cent candy bars… down with candy… in fact… down with everything!”

In Sault Ste. Marie, both the boys’ and girls’ Hi-Y Beaver Clubs decided to boycott the eight-cent chocolate bar, and they encouraged other youth organizations to do the same. The boys would eventually even institute a fine: anyone buying an eight-cent chocolate bar would have to pay an additional sixteen cents to the club. The Chicks and Chucks Club also quickly took up the cause, calling a special meeting at the G. Verdi Temple to hammer out an action plan of their own: “an orderly, yet forceful demonstration.”

Letters to the newspaper poured in, offering support. One candymaker out of Thessalon encouraged everyone to join in the boycott of chocolate bars, confectioners and customers alike, saying, “Refrain from eating candies and I will willingly, in the interest of my country and fellowmen, go fishing for a month and suffer the loss.” The youth wrote in as well, calling on everyone to participate, saying, “Come on citizens of the Sault, back us up and perhaps the price will drop within reason. Remember we citizens have our rights.” Other letter-writers praised the willpower and commitment of the protestors, saying that it cast the younger generation in a positive light.

A few days later, though, media attention would shift. The Toronto Evening Telegram published an article titled “Reds Seen Duping Youth in 8-cent Bar Campaign,” and the rumour quickly spread. As described in the Sault Daily Star, the Telegram alleged that Communist youth organizers were behind the movement, as part of a scheme “to use every possible means of developing and encouraging agitation.” They were careful not to call the participants themselves Communists, but rather claimed that “the students [were] being ‘used’ by Communist agitators” who wanted to “plant a few of the seeds of Marxism.”

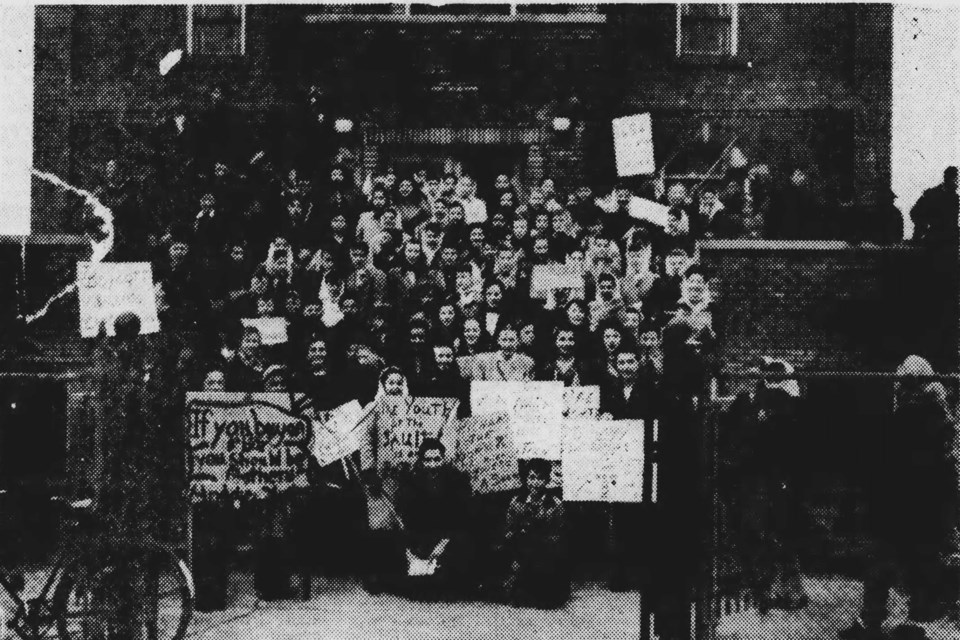

The accusations of communist involvement didn’t seem to deter the youth of Sault Ste. Marie – at least, at first. The same day the article ran in the Star, 500 youth from six to nineteen years of age showed up for a march. Led by Chicks and Chucks president Tony Luciani, their display of resistance spanned James, Albert, and Queen Street, and was complete with “wash tubs, horns, tin cans, cymbals and rattles.” They carried placards, some more aggressive than others – including one that read, in verse, “Whoever buys [an] 8-cent candy bar should be feathered and dipped in tar!” Other signs, less threatening in nature, read, “We’re the People of the Nation, and We Will Stop Inflation,” “A Penny Earned is a Penny Saved, an 8-Cent Bar is a Terrible Shame,” “Down with 8-Cent Candy Bars,” “The Bigger the Cost, the Smaller the Bar,” we’re Teen-Agers not Millionaires,” and, around the neck of a puppy, “I like candy bars too!”

While some merchants were unsupportive or undecided regarding the strike, other candy sellers were on board. The owner of a shop on James Street showed off his five-cent candy bars in his store window and tossed two cartons’ worth of free candy to the youth as they paraded by.

Across Canada, the strikes and boycotts had made an impact, with some candy manufacturers speculating that chocolate bars could be forced off the market; manufacturers would use chocolate in other products instead, focusing on products that still sold. Companies took to the news with justification for why they raised their prices: a war excise tax, an increase in the cost of ingredients, and an increase in the cost of labour. The chocolate industry was feeling the pressure, and it was starting to show.

However, the accusations of communism didn’t go away. Just days after the protest in Sault Ste. Marie, when the chocolate unrest was at its height, Ontario Premier George Drew addressed the issue. He repeated the stance “that a Communist-promoted federation of labour youth had stirred up the juvenile protests against the price increase in chocolate bars,” insinuating that the chocolate bar unrest was part of an overall sinister plan to establish Canada as a Soviet state. The teenagers were stunned by these accusations, and youth organizations began to distance themselves from the protests. Parents became concerned about their children’s involvement in the strikes, not wanting them to become Communists. The protests fizzled.

Nevertheless, many of the teens were proud of what they had accomplished. According to one article about the Chicks and Chucks Club, published in December 1947, the price of chocolate bars decreased by a penny to seven cents – temporarily, at least. The article praised the initiative of the protesters and criticized the negative view of teenagers held by society. Perhaps the author says it best: “For crumb sake, fogies, we get a little tired and disgusted hearing about our shortcomings and wildness. … At least Sault Ste. Marie’s ‘teenagers demonstrated their resentment in an orderly but forceful manner. … Not long [after the chocolate bar protests] the bars went down one cent. How’s that for influence, bub? Teen-timers aren’t going to take things lying down, brother. At least we boycotted the eight-cent candy bar. We’d like to have seen you boycott liquor and cigarettes and the countless other luxuries. It took plenty of willpower on our part, let me tell you that.”

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provide SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more "Remember This?" columns here.