From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

It was the spring of 1932, and wolves were doubtless on everyone’s mind in Sault Ste. Marie. Plans for Wolf Week were underway, with the festival set to occur in July . . . And then, there was Buster, who landed his owner Sam Dodds in court.

Buster had a gentle reputation and seemed accustomed to city life. After being taken from his mother’s den as a young pup, he lived with Sam Dodds, a worker at Algoma Steel. In speaking to the newspaper, Dodds described how the wolf insisted on fresh water, to the point of flipping over his bowl after taking a drink in order to guarantee his bowl would be refilled. Buster inspected all meat before he ate it, and would bury it, wait, and dig up anything that seemed suspect before eating it again. During a food shortage, Dodds fed him corn meal from his bare hands. The wolf could run off-leash with no issues, and seemed, as the Sault Star described, to be “just a big rough dog tamed by kindness.”

Buster was apparently good with kids. Dodds’ own children would wrestle with the wolf. Others from the neighbourhood would even feed him candy, and the wolf would lick their fingers – although Dodds noted that he wished they would not poke their fingers into the cage.

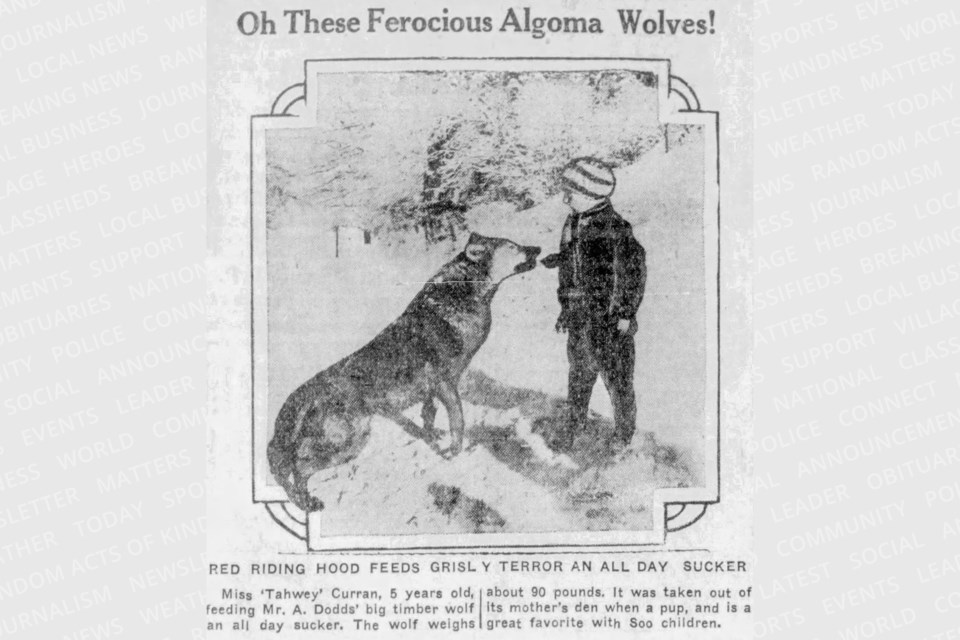

There was even a photo in the Sault Star of five-year-old Catharine Curran, daughter of James Curran, feeding Buster an all-day sucker, an image taken as a publicity photo for the book Wolves Don’t Bite. The newspaper articles of the time described the beast as gentle, taking care not to touch her fingers when he took the candy. In 1962, looking back, Catharine recalled a far more terrifying scenario, describing how “Father darn near fed Marianne and me to a wolf…. Feeding a snarling timber wolf lunging at us at the end of a chain scared the living daylights out of us, no matter what father said.”

Onlookers also were occasionally alarmed by the wolf’s behaviour. In one instance, they were startled to see the wolf snap “viciously at Sam Dodds’ head.” Dodds calmly responded by asking the wolf, “What’s the matter with you? … Hungry?”

From Dodds’ perspective, the only issue was that the wolf had killed several of his chickens. He felt that he could have trained it out of him by striking him, but was not willing to treat him that way.

However, it wasn’t the risk of a bite that landed Sam Dodds in police court: it was the noise. He appeared before Magistrate Elliot in March 1932. The charge? That he “unlawfully and injuriously did have upon his premises a wolf, which continually howls both by day and by night, annoying the neighbours, and thereby commits a common nuisance, endangering the health and comfort of the public.”

Dodds’ neighbours were less than thrilled with the wolf’s presence in their neighbourhood, with three testifying. One told the judge that the wolf’s howls bothered his wife, who was in poor health, to begin with. Another neighbour, when asked by Magistrate Elliot, “You rather like it, don’t you? … Perhaps Mr. Dodds could be persuaded to get two or three more wolves. Would you like that?” said that he would probably move houses if that happened.

For his part, the defence lawyer attempted to put the wolf’s howls in perspective. As far as he was aware, the animal only howled when whistles or horns sounded. Effectively, noted the Star, the wolf “lets the neighbours know when it’s time to change shifts at the paper mill or when a train passes.” None of the witnesses could recall any instance of it howling past midnight. Dodds had obtained a

provincial permit to keep the wolf, and had built a specialized enclosure at his home on Northland Road under the guidance and supervision of a game warden.

Magistrate Elliot ultimately decreed, “We can’t take the howl out of the wolf, so we may have to move the wolf.” However, it’s not clear what Magistrate Elliot’s decision was regarding the wolf.

Regardless, while people turned out in droves for Wolf Week, they were clearly less comfortable with their neighbour owning one that howled as they tried to sleep. The wolf would ultimately die at approximately two and a half years in March 1933 of unknown causes – or, as the Sault Star described it, “passed on to the Happy Hunting Grounds, where traps do not lie in wait for the unwary and man does not break through and shoot.”

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provide SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more "Remember This?" columns here.