From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

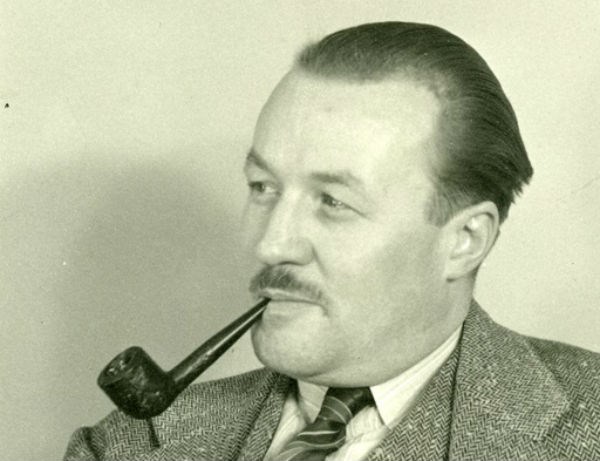

In February of 1966, Dalton Barber, executive at Algoma Steel, was charged with the murder of his wife, who had been found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning.

What followed in May of 1966 was, according to the forensic scientist involved, Sault Ste. Marie’s “trial of the century.”

Due to the prominence of the Barber family in the community, the Deputy Attorney General opted not to involve the Crown Attorney in the case any further. Instead, S. A. Caldbick was brought in from Timmins to serve as special prosecutor and “avoid any possible embarrassment to anyone.”

Barber pleaded not guilty and retained C. Terrence Murphy as his defense lawyer. He was tried by a jury of 12.

Throughout the trial, the courtroom was packed with onlookers, with the Globe and Mail reporting that at one point, 180 people, mainly women, overflowed the room.

Dozens of witnesses were called, many of them connected to each other through the tight-knit Algo Club; these relationships posed a challenge to the out-of-town prosecutor. And, of course, the case gained much media attention. This was in part due to the prominence of the family involved, and in part to the salacious personal details that were coming to light.

According to various news sources, Dalton, for example, had previously approached his doctor, worried for Marjorie’s safety due to her habit of “tearing down the road in her car” in an “unsettled state.”

Dalton and the doctor had gone as far as considering committing Marjorie to a mental institution. Some friends of the family described her as having a terrible temper, which included belittling her husband in front of others; others described her as “a normal, cheerful, positive, stable woman.”

Dalton thought that she had bipolar depression; she apparently had a family history and had been told by her sister that “the only way to get her out of these depressions was to strike her.” Marjorie’s sisters, however, said that this was untrue, that Marjorie was never depressed, and that her family would not have slapped her.

She further claimed that in November of 1965, less than half a month before she died, Dalton repeatedly warned her family “not to be surprised if they received a call in the middle of the night that Marjorie had done something to herself.”

A few hours before Marjorie’s death, the Barbers had quarrelled. She hit him, told him he should “go to a cathouse,” accused him of not bathing for six weeks, and then threw soap at him. According to Dalton, she was unhappy with his heavy drinking, the lack of intimacy in their relationship, and his lack of ambition at the steel plant.

Dalton had been facing some recent difficulties at work. While his brother described him as having “done some brilliant studies” during his time at Algoma Steel, he also revealed that Dalton had struggled with his job duties since then.

According to Dalton’s brother, Marjorie took issue with Dalton’s position in the steel company, feeling that his “capacities warranted a higher position than he had.” The higher-up positions held by Dalton’s family members sparked jealousy.

Moreover, a psychiatrist taking the stand in defense of Dalton said that it was his professional opinion that he was an alcoholic – as exemplified by his liquor consumption, his periods of depression, and his memory loss. The trial even brought in as witnesses the managers of liquor stores who had sold the Barbers alcohol over the years.

Dalton’s brother expressed concern throughout the trial, describing Dalton as being “in a confused state of mind” and acting out of character.

According to Dalton at one point, his life was so miserable that he had attempted suicide that evening, using a combination of whisky and pills. His wife then committed suicide that same evening, Dalton claimed – a coincidence that the prosecution lambasted.

Despite their strained marriage, Barber vehemently denied killing his wife. While recovering in hospital, he went so far as to tell his brother-in-law, Marjorie’s sister’s husband, that he would cut his own throat if people thought he killed Marjorie.

And then there was the matter of Irene Chapman.

Check back next Sunday for the continuing story about this tragic murder . . .

Part 1: The mysterious death of Marjorie Barber

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here