From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

In the summer of 1837 Anna Jameson came to town.

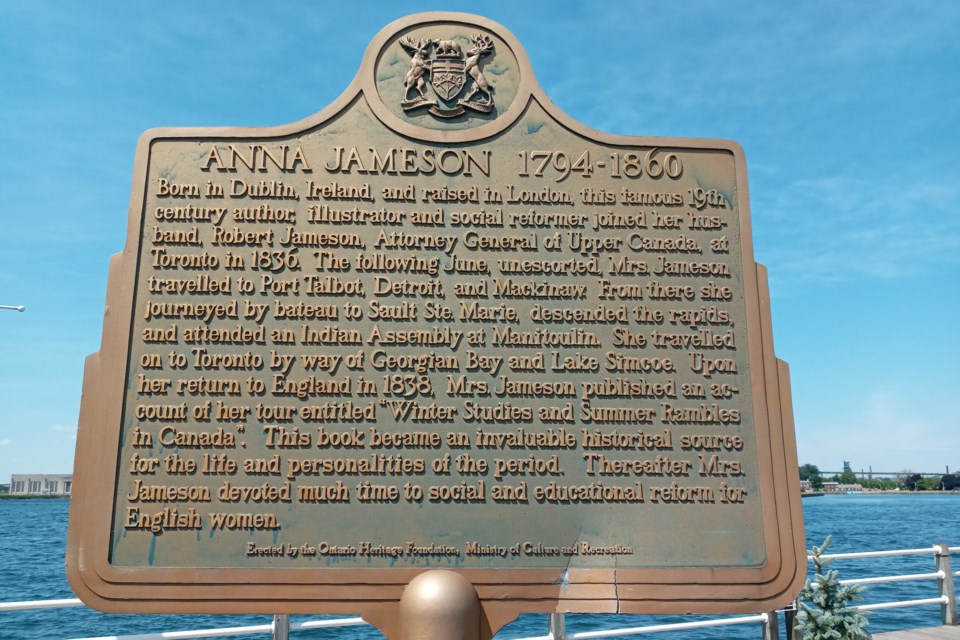

Now, unless you are an ardent student of local history, you might be thinking that you’re never heard of her. However, if you’ve ever taken a walk on the boardwalk downtown, you’ve probably at least glanced at the historical plaque located near the Station Mall that commemorates Anna and her many achievements.

As the plaque states, Anna Jameson (1784-1860) was a famous 19th-century author, illustrator, and social reformer.

She is perhaps best known as the author of the book Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada, an insightful, informative and humourous account of her travels in Upper Canada.

A true visionary, Anna also sprinkled the book with her impressively progressive viewpoints on women’s rights, class conflict, and race relations. It is safe to say that Anna Jameson was well ahead of her time! Winter Studies is now considered the premiere Canadian travel book of the nineteenth century.

If you visit her Wikipedia page, you can read of her many contributions to academia on a wide range of subjects, including feminism, art history, and Shakespearian studies.

What her Wikipedia page fails to mention is that Anna Jameson was the first European woman to ever ride the St. Mary’s rapids.

Here’s the whole story:

Anna Jameson was born in Dublin, Ireland, and raised in England. In 1836 she came to Canada with her husband Robert Jameson when he accepted the position of Attorney-General of Upper Canada.

As a woman possessed with a great intellect and an even greater spirit of adventure, she was not about to resign herself to the life of a housewife during her sojourn in Canada. In 1837, she decided to set out and explore the country. Her travels took her all over Upper Canada and into the United States as well.

During a stay at Mackinaw Island, she heard about a boat leaving for Sault Ste. Marie within the hour. In a near frenzy, she managed to pack up all her things and make it to the boat just on time for departure.

It was a two-day journey on a small Canadian bateau rowed by five voyageurs who hailed from the Sault. Anna described the trip as exhausting, as the crew rowed against both the current and the wind in the hot summer heat. Upon making it to St. Mary’s river, they were immediately enveloped in a cloud of mosquitoes.

They finally made it to the shores of the Sault, thoroughly fatigued, just in time for a heavy rain storm.

Welcome to Sault Ste. Marie, Mrs. Jameson!

In her book, Anna gives detailed descriptions of the settlements on both the American and the Canadian sides.

According to her, in 1837 our fledgling community on the north shore consisted of a meagre trading post belonging to the North-West Company, along with a few “miserable log-huts” belonging to some French Canadians and lawless voyageurs in the employment of the company.

Lower down stood the house of Mr. MacMurray (an Anglican priest) and his wife, “with the Chippewa village under their care and tuition”. There was also a little missionary church and school house.

And that was it, and that was all.

Even still, there were two things that Anna found very impressive about Sault Ste. Marie:

The first was the quality of the whitefish. Anna described eating them four times a day, declaring that they were not only plentiful but also the best-tasting fish she had ever had.

The second was the St. Mary’s Rapids.

Anna was immediately entranced by the might and beauty of the rapids. If the rapids of Niagara were like a monstrous tiger at play, she wrote, then the rapids at St. Mary’s were like an exquisitely beautiful woman in a rage, but with “no terror in their anger, only the sense of excitement and loveliness.”

Anna wrote that the descent of the rapids was about twenty-seven feet over three-quarters of a mile, but that the rush began above the falls, and the turmoil continued below the falls, so that “the eye embraces an expanse of white foam measuring about a mile each way”.

During her stay, Anna had an opportunity to witness several fishermen from the Chippewa tribe as their canoes traversed the “boiling surge” at the bottom of the rapids, the boats “dancing and popping about like corks”.

She also heard stories about how some members of the Chippewa tribe were unafraid to descend the rapids in their little canoes, learning to find safe passage amidst the swirling waters and jagged rocks. She soon decided that she wanted to experience this adventure first-hand.

(It should be noted that, according to Bouchette’s Canada, published in 1815, it was inadvisable to descend the St. Mary’s Rapids in a boat. The book recommended that travellers portage instead, which involved a two-mile hike, but avoided the dangers of the falls. But Anna Jameson was not one to eschew danger.)

Without hesitation, Anna put her plan into action.

A friend of hers found a local Indigenous man who was willing to take her down the rapids in his boat, which was just a small fishing canoe. Ascending to the top of the falls with her fellow adventurer, she climbed into his canoe, and down they went “with a whirl and a splash”.

Using his expertise, the intrepid navigator steered the canoe with great dexterity, keeping the head of the canoe to the breakers. Anna was in the back of the canoe as it raced downstream, filled not with fear but rather giddy excitement as the boat narrowly avoided the rocks, the “touch of which would have sent [them] to their destruction”.

The entirety of Anna’s aquatic adventure lasted only seven minutes, but she would remember it for the rest of her life.

Upon safely reaching the shore at the bottom of the rapids, she celebrated with her new Indigenous friends, who were delighted by Anna’s daring and determination. She was declared to be “duly initiated” as an honourary member of the Chippewa tribe, and “adopted into the family by the name of Wah,sàh,ge,wah,nó,quà”, which according to Anna, translated roughly as “woman of the white foam”.

Mrs. Jameson’s stay in the Sault was short, but she established many close relationships while in town.

After departing she travelled first by bateau to the Manitoulin Islands, followed by journeys to several islands in Lake Huron, before finally travelling back to Toronto. In 1838, she returned to England, where she published Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada.

Afterwards, she devoted a great portion of her life to educational and social reforms for women.

A copy of Anna’s book can be found in the Local History collection at the James L. McIntyre Centennial Library. Winter Studies is also available to read for free online. Please note that the unfortunate title change was the choice of the publishers, not Anna’s!

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here