From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

Unlike many of the superstitious sailors of the open seas, Captain James McMaugh of the Algonquin steamer turned his eyes and ears away from tales of premonitions, omens, and the supernatural. However, on the afternoon of Nov. 21, 1902, about fifty miles southeast of Passage Island on Lake Superior, he witnessed something unexplainable.

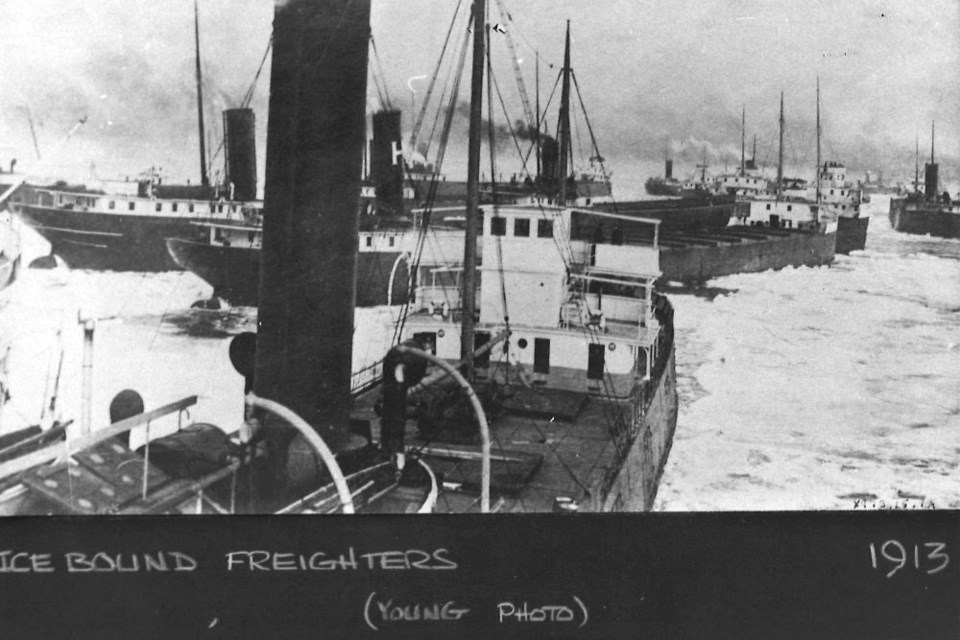

The Algonquin was one of several ships involved in the grain trade, carrying bushels of wheat from Fort William and Port Arthur (currently known as Thunder Bay) to lower lake ports.

The Algonquin was heading north when McMaugh spotted another steamer, the Bannockburn, travelling south. The weather that afternoon was hazy, but McMaugh identified the 245-foot Bannockburn immediately.

He noticed the Bannockburn was chugging along without either of her additional barges, but nothing else seemed out of the ordinary.

Two or three minutes later, McMaugh turned his attention back towards the Bannockburn, but the vessel had vanished. Although the haze was indeed disorienting, the ship was too close in distance to turn completely invisible.

Heading into Port Arthur, the Algonquin battled harsh winds and crashing waves and by nightfall, Lake Superior was engulfed in a ferocious storm.

That night, yet another steamer called the Huronic was travelling north.

Fred Landon was a scholar onboard who kept daily diaries. For his entry on Nov. 21, he noted “At night we had the worst storm of the season.” On the 22nd, he explained, “During the storm of last night our engines sustained slight damage which they are repairing today.” According to sailors on the Huronic, the ship had passed the Bannockburn through the night. Unbeknownst to the crew, it would be the last time anyone ever saw the Bannockburn.

On Nov. 28, Landon’s diary noted “Heard today of the missing Bannockburn. This boat we passed on the night of the 21st.”

On Nov. 20, the day before the storm, the Bannockburn was “under the spouts” at Port Arthur, loading 85,000 bushels of wheat destined for Midland, Ontario.

The steamer planned to sail across Lake Superior and reach Georgian Bay. With winter coming, ice was already beginning to freeze the shores of Superior, but 37-year-old Captain Wood believed his vessel could still make a return trip.

The Bannockburn was built in 1893 in Middlesborough, England. Her rivets were reportedly set and hammered by the greatest shipbuilders in the world.

Weighing in at 1,620 tons, she was named after the Scottish underdogs led by Robert Bruce who defeated Edward II’s larger English force at Bannockburn in 1314. The victory assured Scotland’s continued independence.

The Bannockburn carried a very young crew of twenty men. The only married sailor among them was 33-year-old Chief Engineer George Booth. His subordinates were 24-year-old Charles Selby and 22-year-old William Chalkley. The average age onboard was somewhere between 17-20.

The vessel originally departed from the Canadian Ship Canal in Kingston and estimations believe the Bannockburn left Port Arthur around 9 a.m. on the morning of the 21st, placing her right where McMaugh last spotted her that afternoon.

News of the missing ship soon spread, and numerous conflicting and unexplained reports surfaced within the week.

On Nov. 27, the Fort William Times Journal announced that Mr. Sellars, the elevator superintendent at Port Arthur, received word that the Bannockburn was resting behind State Island, just twenty miles out from Jackfish Bay. Sellars immediately denied the whereabouts of the ship, claiming “I have heard nothing of her. Absolutely nothing.”

The newspaper later declared that the Bannockburn was washed ashore north of Michipicoten Island revealed through a telegram by a steamer known as the Germanic. Mariners assumed the missing ship was trying to avoid the worst of the storm only to be thrown on land by the towering waves.

Back in Kingston, a telegram received from Chicago stated “The Steamer ‘Bannockburn’ has been located on the North Shore of Lake Superior, opposite Michipicoten Island. Crew safe.”

Meanwhile, in Ottawa, another telegram claimed the Bannockburn was stranded on the shores of Michipicoten Island itself.

However, the veteran mariners in Sault Ste. Marie with years of experience sailing Lake Superior refused to believe any of the reports.

Firstly, the weather had cleared since the night of the storm, so even if the Bannockburn was washed ashore, smaller lifeboats could’ve easily travelled to Michipicoten Harbour.

Furthermore, the trek by foot on land would’ve taken two days at most. Finally, and most significantly of all, Michipicoten reported no signs of the Bannockburn or her missing crew.

The Great Lakes Towing Company’s wrecking tug was ordered to locate the Bannockburn. After travelling along several routes, nothing was found.

The missing ship’s insurers then chartered another tug to search between Caribou Island and Michipicoten Island.

Meanwhile, upon further investigation, there was zero evidence of a telegram ever being sent from the Germanic to Chicago. When pressed for information, the Germanic officers confirmed there were no sightings. Had they spotted a stranded ship, the crew insisted they would have tried to save as many lives as possible.

Upon returning to Kingston with no signs of the Bannockburn, the ship’s insurers released a statement declaring “It is supposed that the steamer is stranded on Caribou Island.”

Caribou Island was surrounded by sharp shoals along its northwestern edge. The consensus was that the ship could’ve smashed into one of the dangerous reefs during the storm.

If Captain Wood had been searching for the island’s lighthouse for guidance, he would, unfortunately, have been out of luck. Even though ships were set to sail into early December, the lighthouse on Caribou Island was forced to shut down on Nov. 15.

When an American whaleback ore carrier called the Frank Rockefeller arrived in Sault Ste. Marie, the captain reported passing through a large amount of wreckage off Stannard Rock, southwest of Caribou Island.

There was no evidence that the debris belonged to the Bannockburn, but as the only ship missing on Lake Superior, it was considered highly suspicious.

For McMaugh, captain of the Algonquin, he was convinced the Bannockburn had burst her boilers and exploded on the afternoon of the 21st, in the short window of time between her first sighting and her disappearance minutes later. Though close enough not to become invisible in the hazy weather, the distance was vast enough that the explosion would not be heard aboard the Algonquin.

However, the crew of Huronic remained steadfast that it was indeed the Bannockburn they had spotted on the night of the storm.

The Daily Whig announced that all hope was lost in ever finding the Bannockburn, stating “It is generally conceded that the missing steamer is not within earthly hailing distance, that she has found an everlasting berth in the unexplored depths of Lake Superior, and that the facts of her foundering will never be known.”

In a stranger statement, Captain Gaskin of the Montreal Transportation Company justified that “She could not have been in a collision, since no other ship is reported missing or damaged. That leaves only three other possibilities… she either burst her boilers, hit a rock or shoal, or… her machinery went through her bottom!”

British steel vessels had been sailing for more than half a century without any reports of rusting hulls, and the Bannockburn was only nine years old when she disappeared.

Experts came to the conclusion that the Bannockburn was overloaded. 85,000 bushels of wheat would place her beyond the safe limits for that time of year.

The mystery peaked in December when a steel plate from the bottom of a ship was discovered in the drained Canadian locks in Sault Ste. Marie. The vast majority of mariners believed the plate was from the vanished Bannockburn.

Many months later, a single life preserver and a lone oar were discovered on the American shores of Lake Superior.

In the years following the disappearance of the Bannockburn, many superstitious sailors compared her to the legendary Flying Dutchman, “a vessel that vanished off the Cape of Good Hope in a gale, only to reappear on the seas as a mysterious phantom ship, most frequently sighted during the night watches as she beats to windward on her endless voyage.”

On stormy nights, the Bannockburn is known to have been sighted, still chugging her way down Lake Superior, searching endlessly for the Caribou Island lighthouse.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here