Most Second World War prisoners of war (and veterans in general) are reluctant to speak of their wartime experiences.

So too are Japanese-Canadians who were relocated from Canada’s west coast and interned during the war for national security reasons.

Toronto-based Mark Sakamoto, a lawyer by training, is the author of a book titled Forgiveness: A Gift from My Grandparents, which tells the story of Ralph MacLean, his maternal grandfather, who was a Canadian prisoner of war in Japan during the Second World War, and Mitsue Sakamoto, his paternal grandmother, and her Japanese-Canadian family who were interned by the Canadian government in Alberta.

Sakamoto’s parents first met at a high school dance and later married.

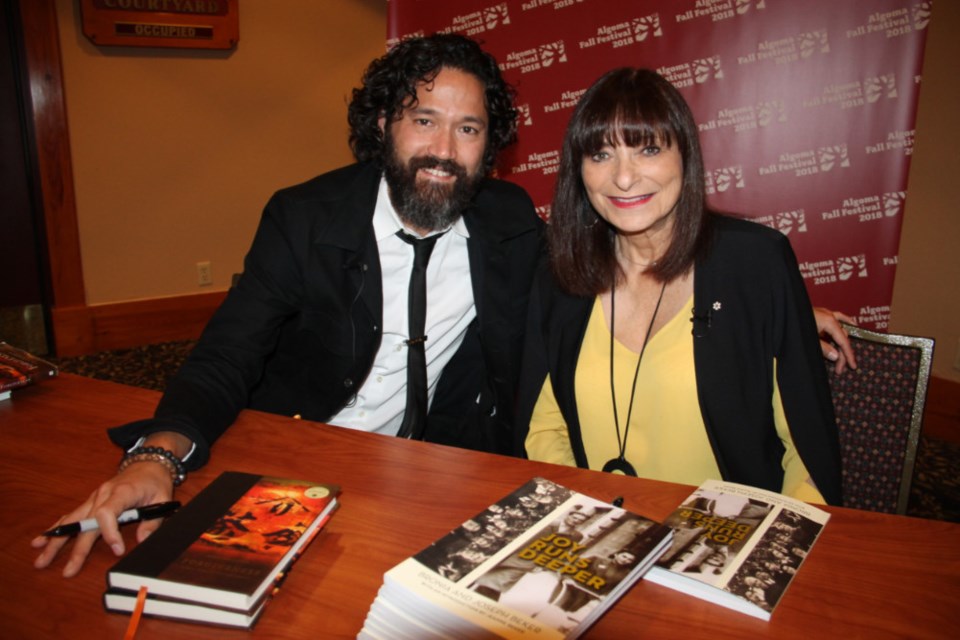

Fascinated readers listened to Sakamoto and Jeanne Beker, Canadian fashion journalist, at the Sault’s Water Tower Inn Sunday, where the two discussed the book, Sakamoto reading excerpts from it, the pair signing copies of it at Forgiveness: A conversation with Mark and Jeanne, an Algoma Fall Festival event.

Forgiveness: A Gift from My Grandparents won the Canada Reads 2018 competition, and is being adapted for a CBC TV miniseries and stage play.

Beker shared how she can relate to Sakamoto in the sense her family also experienced wartime horror, her parents being Holocaust survivors.

“My parents couldn’t stop talking about it. It was cathartic for them to talk about it,” Beker said, noting by contrast, Sakamoto’s grandparents were “stoic” about their own experiences.

“Most veterans didn’t talk about it. My grandfather wanted to protect himself. It was bad enough he had to relive it in his dreams, and (veterans) also wanted to protect their families. They didn’t want to talk about how truly harmed they were,” Sakamoto said.

“And, on the Japanese-Canadian side, very interestingly, almost to a person, they don’t talk about the internment very much. They have this saying, ‘It happened, can’t help it, move on,’ and that’s almost uniformly what they would say.”

Nevertheless, author Sakamoto has learned a great deal about the suffering on both sides of his family.

“The racism and political pressure in Canada occurred primarily in B.C. They (Japanese immigrants of the early 20th century) were an easy target...hate always comes wrapped in a flag. Those forces that wanted Japanese out with the ‘go back home' mentality used Pearl Harbour as an excuse,” Sakamoto said.

Following the decisive Battle of Midway, in which Japanese naval forces suffered a huge blow at the hands of the U.S. Navy, Sakamoto said Canadian internment of Japanese immigrants and those of Japanese descent intensified in 1943.

“Folks used the war and national security as a means to move all Japanese-Canadians 100 miles from the coastline.”

Sakamoto said the RCMP and Canadian military establishment have since testified under oath “there was not one single Japanese-Canadian even so much as charged with any sort of offence (during the war)."

“This was all a ruse. It was all fake news. It was all made up because folks in British Columbia didn’t like Japanese folks. They didn’t look like them, they didn’t eat like them and they were really good fishermen.”

At the same time, vicious treatment of Canadian and other Allied POWs during the Second World War is a well-known true story.

There were 1,975 Canadian troops sent to Hong Kong to help British, Indian and Hong Kong forces defend the territory against a large Japanese invasion force in December 1941.

Canadian troops, Sakamoto said, were “so good, and so tough.”

Two hundred ninety Canadian troops died in that invasion, the rest sent to POW camps in Japan.

Two hundred sixty-seven Canadians died in those camps.

“What (the surviving Canadian POWs) lived through was so horrific,” Sakamoto said.

Ralph MacLean, his maternal grandfather who survived the horror of the Japanese camps, is now 96. (Sakamoto’s grandmother is deceased.)

MacLean, Sakamoto said, survived a journey on a "hell ship" (fed only sloppy rice and living in excrement) from Hong Kong to Japan, and while in captivity in Japan, suffered from burning feet (a condition known as neuropathy, which affected up to one-third of Far East POWs in the Second World War), underwent beatings, tried to sleep on a concrete floor, experienced filthy living conditions, malnutrition, and witnessed the heartbreaking, slow deaths of some of his comrades.

Interestingly, Sakamoto said as soon as food and other essential items were supplied to liberated POWs by the Allies at the end of the war, his grandfather MacLean reached first for a Bible from an aid barrel, before reaching for food.

Sakamoto said his Japanese grandparents were forced to leave B.C. with only two small tea boxes to carry their belongings.

The author discovered one of the tea boxes after searching through his grandfather’s home when he passed away, 60 years after being forcibly sent away from B.C.

The box was restored by Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum and now sits in Sakamoto’s home, and is photographed on the cover of Forgiveness.

“It reminds my children everything can be taken away. They live very privileged lives, but everything you own can all go, for terrible reasons or whatever. It means nothing! The only thing that matters is what you put in your head or your heart. I really love that box and keep it close,” Sakamoto said.

Beker said Sakamoto's book should be taken as a warning against what hatred does between different cultures, but despite its heavy backdrop, it is a hopeful story of how his grandparents and parents were able to get to know each other and marry, exercising forgiveness as the key to preventing hatred from taking root over Second World War experiences.

“I assure you the book is uplifting in the end,” Beker smiled, addressing Sunday’s audience at the Water Tower Inn.

For a listing of other Algoma Fall Festival events, check out the festival’s website.