I have written extensively about how Ontario has been mismanaging moose for at least 25 years. This has resulted in a decline in the moose population to 70,000 animals and hunters to less than 40,000 from 100,000 each in 2000. I presented the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) evidence that the Selective Harvest Program, as implemented, was not working and offered plans to fix it with a seven-point plan, as well as addressing the lack of moose in the bush and addressing issues with the tag system.

This information was provided to the highest levels within MNR so they cannot say they didn’t know there was a problem. No one has challenged the evidence that was presented so presumably they do not disagree with it.

The good managers I have known welcomed criticism. It opened a dialogue. It allowed them to explain their position, to better understand problems, and possibly find solutions to fix them.

In spite of the evidence, no one from MNR or the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) has contacted me. I think, like truculent children, they will refuse to accept anything I say simply because I said it.

That speaks volumes to the quality of the leaders. Don’t confuse me with facts. My mind is made up.

I learned, probably from my truck, also retired, that you can only tinker and fix things for so long before you have to recognize they will never work and need to be replaced with something that will. This certainly applies to moose management in Ontario. The replacement is more of attitude and strategy than a massive overhaul of the fundamental program. I believe the current Selective Harvest program has the potential to be the best program in North America. It just needs to be used correctly.

My recommendations, as judged both by support for, and the absence of criticism in reader comments, suggest that they are well received. Comments from my contacts in academic and moose management circles also support the recommendations.

To this point there is not the slightest recognition from MNR or the OFAH that there is even a problem. The only solution offered was a plan to make the tag distribution system more inefficient and to punish hunters for trying to get the tags they want without losing points. This is so MNR can provide more killing opportunities to speed up the population decline.

Both organizations supposedly have professional wildlife managers who have had years to review the information and act. They do not need further study. They do not need more “listening sessions” focused on hunters who, yet again, want more moose and more tags. MNR should not be dismissing the interests of the majority of Ontario residents who don’t hunt or the businesses that benefit from activities associated with moose hunting.

I’m not criticizing hunters. Their expectations are reasonable, and consistent with the history of moose hunting and the expectations of other Ontarians, at least as far as more moose goes. I’m not criticizing MNR field staff. I have found them to be interested and dedicated to their profession.

I’m criticizing MNR regional and senior biologists and managers, the supposed leaders, for interpreting the message as “more tags immediately” rather than “more tags in the long term through effective management.” I’m criticizing them for knowingly ignoring the evidence of overhunting and general mismanagement. I’m criticizing MNR for sugarcoating and trying to distract from the problem with high computer estimates of the population and low computer estimates of the potential of Ontario forests to support moose. These do not agree with other known facts.

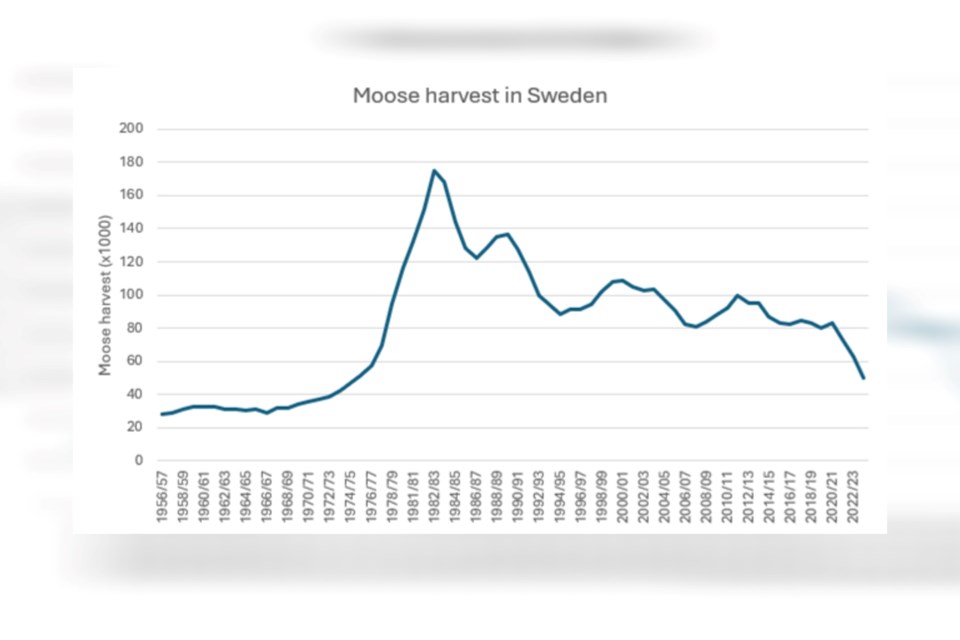

I have frequently referred to the very successful Scandinavian management system that places more emphasis on the harvest of calves. A colleague from Sweden recently provided this chart of the moose harvest and noted that 50 per cent of their harvest was calves.

They implemented selective harvest in the 1960s and it created a population explosion. That is what could happen in Ontario with effective harvest control, but there are some major differences.

Ontario has more wolves and First Nations hunters. Both must be included in a total and effective management system. Ontario also has brainworm carried by deer.

The Scandinavian numbers may be higher than what Ontario might achieve, but the principles are the same. It may be possible to address disease with research, as Ontario did with the rabies vaccine that is now used around the world. The important thing is to rebuild the population and use adaptive management to determine optimal population and harvest levels.

The decline from the peak was the result of habitat deterioration before they got the explosion stopped. The slow decline thereafter is the result of a variety of relatively small factors like changing habitat and increasing wolf numbers (which they plan to adjust).

In Sweden, 64 per cent of moose mortality is through hunting. Twenty-one per cent is from wolf and bear predation (in equal numbers), and 11 per cent is from motor vehicle accidents.

Aside from the obvious success and high calf harvest, the other two important aspects of their system are that management is based entirely on hunter supplied information. They understand that it is in their own interest to accurately provide observations on the herd status and harvest.

Misinformation leads to mismanagement. That should be a lesson to hunters and to MNR managers for failing to create a hunter supported harvest assessment system. Sweden has no aerial inventory program, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. The other aspect is that the changes are anticipated and being addressed through adaptive processes.

Having a long history as a moose manager, and skills in areas where there appears to be gaps within MNR, I offered to assist them with two aspects of the program. I wrote about the poor state of moose information.

Good decisions cannot be made without good data. It is acquired from two main sources: aerial inventory plots and hunter questionnaires (now mandatory reports). These records should be in three files, possibly with one or two sub-files. There should be one for population information, one for harvest information and one which combines the two into harvest management plans and the results of those plans.

Raw data should be summarized first at the Wildlife Management Unit (WMU) level, and from there, many information products can be created. After analysis, there should be only one “answer” to any “question”. I found four different sets of moose harvest results and was provided with eight files of aerial survey plot data. They had several different format, lots of missing and incorrect data. The unique link joining several files, didn’t work, making them useless.

I was seconded to lead the development of a Wildlife Management Information System (WMIS) in 1999 (to avert the Y2K disaster). The plan was for a fully integrated and effective system — data entered once, standard analysis, with all possible information products produced automatically, and all under the control of a knowledgeable Database Manager.

It was never completed. Having time on my hands and wanting to challenge my brain, I created most of that information system. It has about 75 tables with graphs, and the possibility of many more as other systems are added.

Below are several graphs chosen to show the power of good information. Differences among zones (the old administrative regions) suggest different approaches are required. Survey conditions like snow crust, hours since snowfall and temperature are believed to influence the quality of estimates.

This data has been collected for 50 years, and no one has summarized it, let alone attempted to use one of the powerful modelling tools to “correct” estimates. My simple assessment suggests that there is little correlation between moose density and the survey conditions, but I compared them one at a time. A sophisticated model would look at them all together. If they aren’t worth analysing or can’t be used, then get rid of them.

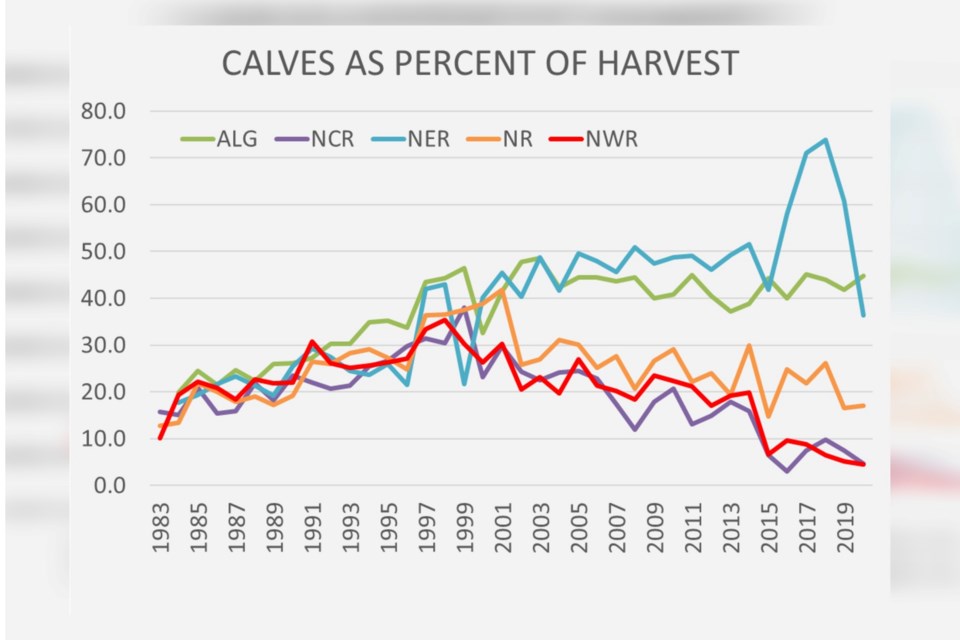

MNR has legitimate concern about overharvest of calves, but only in the southcentral area of the province, the former Algonquin and Northeastern Regions. That concern does not justify the provincewide calf protection strategy that resulted from the 2019 review (1).

It also shows that the calf harvest in three of the five zones is declining at the same rate as the adult harvest. Total overharvest, not calf overharvest, is the problem. It is worth noting that zones with the highest calf harvests are also the zones with the highest moose and hunter densities at one time. This creates perfect conditions for excessive harvest.

Population density also changes across the province. Again, it suggests that one provincial strategy is not appropriate. If you are wondering about my street creds, I set tag quotas in the Northwestern Region from 1983 to 1999 (the red line). The population was estimated by real standard surveys, not increasingly more intensive ones.

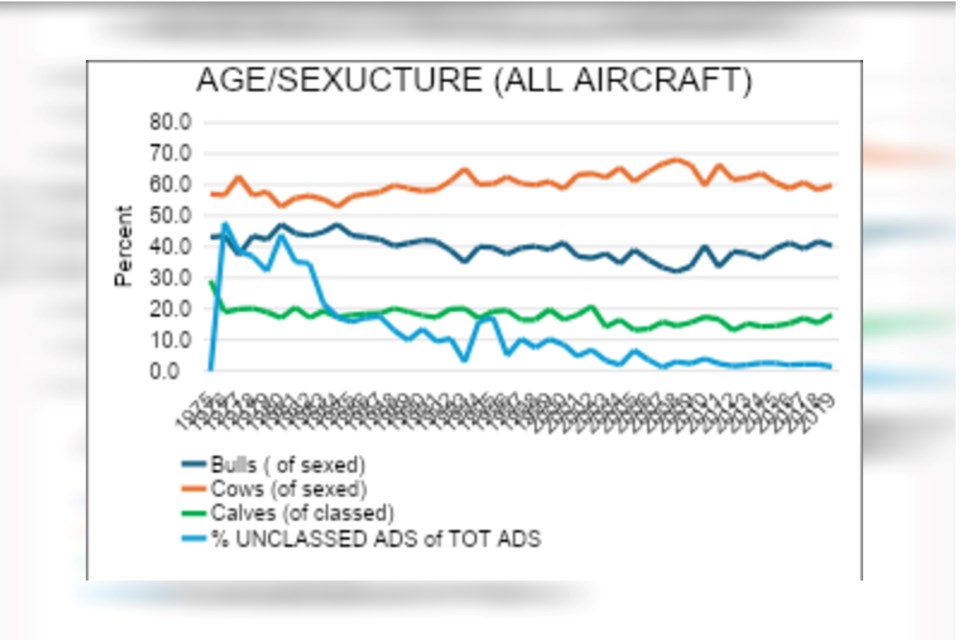

While the 2019 review expressed concern about an excessive calve harvest, it has not greatly affected the ratios in the population. It seems that fear was exaggerated. It is difficult to interpret early bull-to-cow ratios because of the high proportion of unclassed adults when using fixed-wing aircraft. I expect they have remained close to the desired 60-per-cent-cow-to-40-per-cent-bull ratio for optimum productivity. A small decline in calves appears more closely related to the decline in bulls. The problem may be too few bulls to breed all the cows. Killing more cows to balance the herd is just irrational in a declining population. Killing fewer bulls is a better way to achieve balance.

It appears that I am still the only person with a vision of what a proper information system could do. I offered to help MNR complete that system, starting with the work I have done. It doesn’t surprise me that I haven’t had an answer.

The second thing I offered to help with was implementing the changes needed to turn the harvest management system into an effective one. Hunters are demanding a change in the management system.

There is no evidence, either in theory or in real evidence, that the current program has any possibility of succeeding. Since 2014 (2), I have advocated bringing all the principles of Scandinavian selective harvest to the open hunting system in Ontario, not just the name.

The licensing system and controlled calf harvest was adopted in 2020. Retaining group applications and implementing direct harvest control (one-tag-per-moose) were not. Nor was the inclusion of First Nations as co-managers.

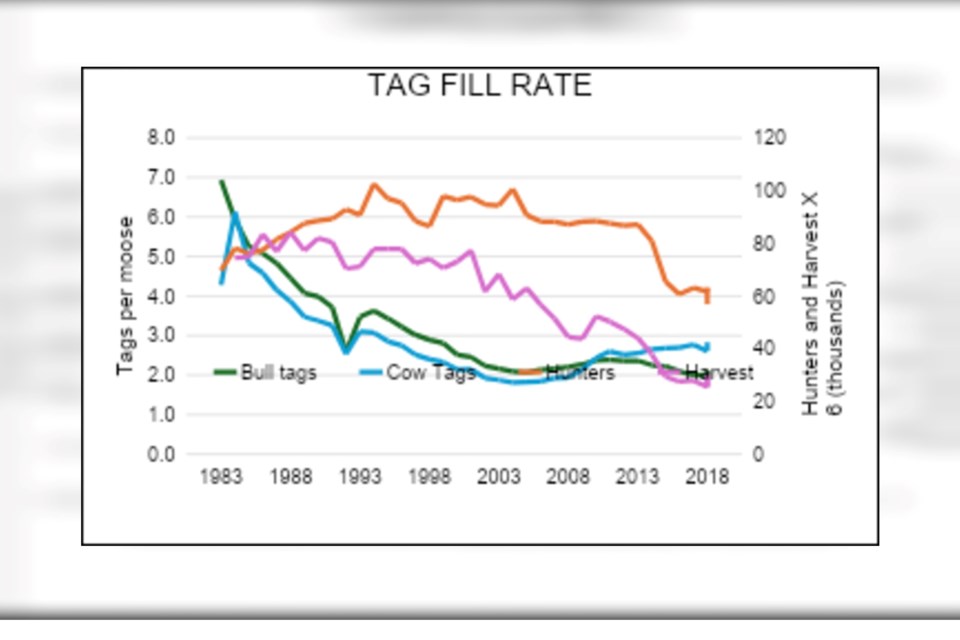

The Achilles heal of Ontario management is the use of tag fill rates. Multiple tags per moose do not control the kill. As the following graph shows, tags were reduced as hunters increased and helped to fill them. After 2000, with the continuation of excessive harvest plans, the kill could not be achieved, so tags were increased to try to kill more moose. Again, this is not a particularly wise strategy. While cows should be about 40 per cent of the bull harvest, 50 per cent more cow tags are being offered.

If Ontario followed my recommendations, it would initiate population growth if not an explosion. A change in strategy would require MNR to admit failure. Regrettably, evidence suggests that they would rather let the resource be destroyed than do that.

I have offered to take my recommendations to the public. That way, I’ll shield them, and deflect, or bear the brunt of criticism. Regardless, I have little doubt that Ontario managers will have to accept my recommendations at some point. It becomes a question of whether it is before or after total collapse of the moose population.

That sounds like a pretty arrogant statement. I worked damn hard as an MNR employee, and still do, at collecting the information and evidence that formed my beliefs — “evidence-based opinions” if you prefer. I think constantly about the problems. I’m not arrogant. I’m confident. Absolutely damn confident.

Because MNR (with OFAH support) adopted but modified several of my past proposals with detrimental results, I am the only person qualified to explain and justify my recommendations. Of course, this offer alleviates MNR of the blame if my recommendations are rejected by the public. I willingly accept that. It will save them more ridicule if they screw up without my help.

I would not accept compensation for my participation. I don’t want to be perceived as working for or promoting an MNR proposal. Instead of asking the public what they want, and evidence suggests cannot possibly be provided with the current state of the resource, it is time to offer a complete and fully integrated management system that should benefit everyone through an increased moose population.

I have no problems with challenges to, or discussion regarding my recommendations. I welcome alternatives if they can be demonstrated, even theoretically, to work. Ontario has tried almost everything without success, and I was there for most of those efforts. It is time to trade in the old, seriously failed model for a new and functional one.

If my offer is accepted, I would recommend an open public meeting in every district, and an internal one for district staff. While moose live in the North, most hunters live in the south. There appears to be a high level of misunderstanding about moose management within MNR. They can’t support and explain a program if they don’t understand it. It will be interesting to see if MNR is willing to accept my offer or continue to do nothing about the identified problems.

If they don’t accept my offer, I’m still willing to talk moose with any group willing to pay expenses or set up a video conference. I just have to figure out the technology to achieve the latter.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both Internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the search bar at Sudbury.com.

References

1: BGMAC (Big Game Management Advisory Committee). 2019. Moose management review. https://www.ofah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MMR-engagement-presentation-May182019-compressed-002.pdf

2: BISSET, ALAN R. 2014. Moose management in Ontario: an alternative strategy. https://tinyurl.com/Moose-alternative.