This article, written by Ahmed Al-Rawi, Simon Fraser University, originally appeared on The Conversation and is republished here with permission:

During the politically sensitive weeks before an election, public discussions often intensify. In Canada this summer, the buzz has included discussions about the spread of bots on social media.

Bots are automated social media accounts that are programmed by humans to send hundreds and sometimes thousands of messages a day. News stories are written to inform and possibly warn Canadians about the existence of these bots, which are currently at the centre of public and academic debates, sometimes reaching the level of moral panic.

Curious about this issue, I recently decided to examine a large dataset that I’ve been collecting from Twitter. My examination shows that the spectre of bots is being weaponized by all sides to discredit opponents and possibly silence them.

Using a digital media platform, I collected 1,733,852 tweets with the hashtag #CDNpoli that were posted by 163,241 unique users. This hashtag, an abbreviated version of “Canadian politics,” is among the most popular used by social media users when they’re tweeting about Canadian politics.

A spike following SNC-Lavalin news

The Twitter data was collected from May 23, 2019, to Sept. 4, 2019. The day of Aug. 14 had the highest number of tweets so far — 39,382.

The spike coincided with the breaking news that Prime Minster Justin Trudeau broke ethics rules in the SNC-Lavalin affair.

In my view, this shows a healthy engagement in political issues on social media because democracy always needs to hold the powerful accountable.

To move forward in my project, I extracted the most popular stories in these tweets (most retweeted) and the most active users (those who tweet more than others) using two codes in Python, a program for processing large datasets.

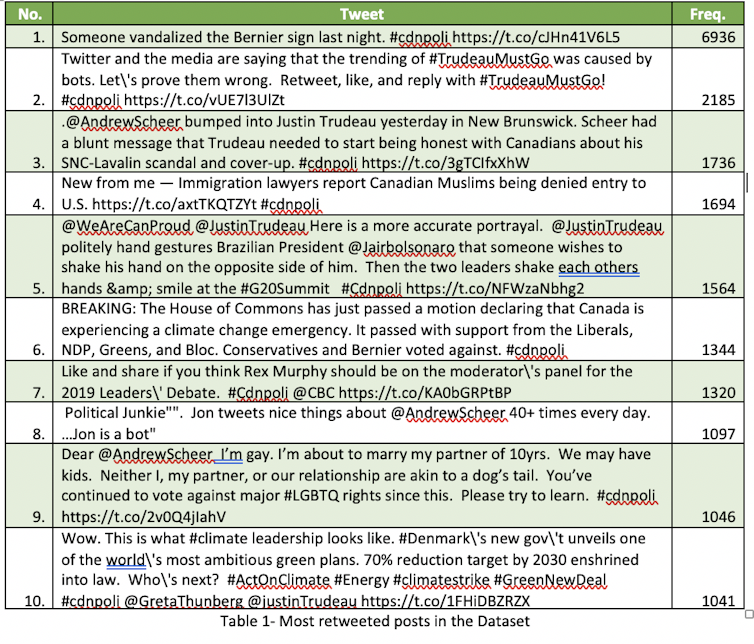

The following graph shows the most retweeted messages and their frequencies. They pertain to news reports and partisan messages mostly praising or attacking Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Conservative leader Andrew Scheer and Maxime Bernier, head of the People’s Party of Canada.

But there are two other notable features.

First, there are many references to climate change in the discourse on the Canadian election (tweets No. 6 and 10). Using a machine learning technique, I identified the most important topics. Climate change action is at the top — something that requires further scholarly attention.

Second, there are references to bots (tweet No. 2). The tweet challenges some claims that the popular hashtag #TrudeauMustGo is generated by bots, while tweet No. 8 accuses an active supporter of the Conservative Party of Canada of being a bot.

From my preliminary evaluation, the term itself seems weaponized to discredit opponents and possibly silence them just for being active users. In fact, this technique is not unique to Canada, for other weaponized terms like “fake news” in the United States and “electronic flies” in the Middle East are used in similar situations.

No evidence

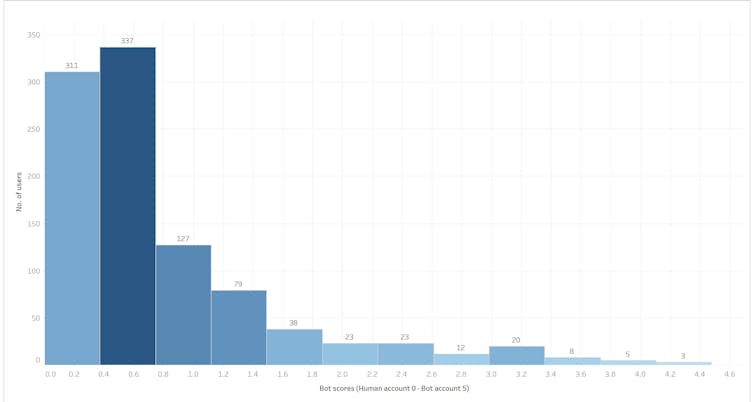

The problem here is that these accusations are made without evidence. One of the users accused of being a bot scored 0.4 out of five using a digital tool called the Botometer, which is often employed to identify individual and bulk users based on several criteria. It gives a score ranging from zero for being human to five for being bot, and we can manually check individual users by using the Botometer website.

To understand whether these users who tweet about Canadian politics are in fact bots, I examined the most active 1,000 users to determine their likelihood of being bots using a Python code.

In total, those active users tweeted 633,105 times, constituting 36 per cent of the total dataset. I focused on these active users because my initial suspicion was that many could be mostly bots due to their high activity. But I was wrong.

The top user, for instance, tweeted 5,345 times promoting anti-Conservative views using the hashtag #CDNpoli. A closer examination showed this user is human, not a bot. It scored 0.6 out of five on the Botometer.

Private accounts

From the 1,000 users examined, there were 14 accounts that were not detectable mostly because they were suspended or their accounts were private. The following graph shows the Botometer scores of the users I examined.

As it turns out, only 16 users of the 163,241 I examined might be categorized as bots, a fairly insignificant number in comparison to other studies that showed a large number of bots in political discussions on social media, especially among active users.

The highest scoring user (4.4 out of 5 on the Botometer, indicating the user is a bot), for instance, tweeted more than 49,000 times from May to early September with messages supporting the Conservative Party. Another user, @EnvironTwitBot, tweeted more than 78,924 times and describes itself as follows:

“I am a twitter bot created for a dissertation about online communities and predictive algorithms.”

The remaining bot-like users have different political positions and affiliations.

Again, these few accounts should not cause any concern because there are only few of them, and this small-scale examination revealed that the most retweeted posts on Canadian political issues are from genuine and diverse Twitter users.

Claims that tweets on the Canadian election are the work of bot accounts, without empirical evidence or verification, need to be taken with a grain of salt. Political activists from many sides seem to be using the bot argument to attack and discredit their opponents, with the possible goal of silencing healthy political debates on social media.

Ahmed Al-Rawi, Assistant Professor, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.