Sometimes—for good reason—a story slips your mind until something triggers its return, even without a bump on the noggin.

So here it is—an organic requiem of sorts, a natural obituary

As Bruce Cockburn asked in his 1988 song: "If a tree falls in the forest, does anybody hear?"

It was a very humid and hot day on July 11, 2020, when the pilgrimage started.

Certainly, there would have been a resonating sound or vibration when the tallest white pine tree in Ontario fell in June of 1997 during a windstorm.

Five years ago, I set out on a quest to find this mammoth tree again, 23 years after it had finally come to rest. I had seen it alive and well before its demise and was curious about what it looked like now—horizontally. This one lived a long existence on the back roads.

It was a trek to pay homage to the province’s arboreal emblem. Trees are our largest plants and are vital to our survival and well-being, physically and mentally.

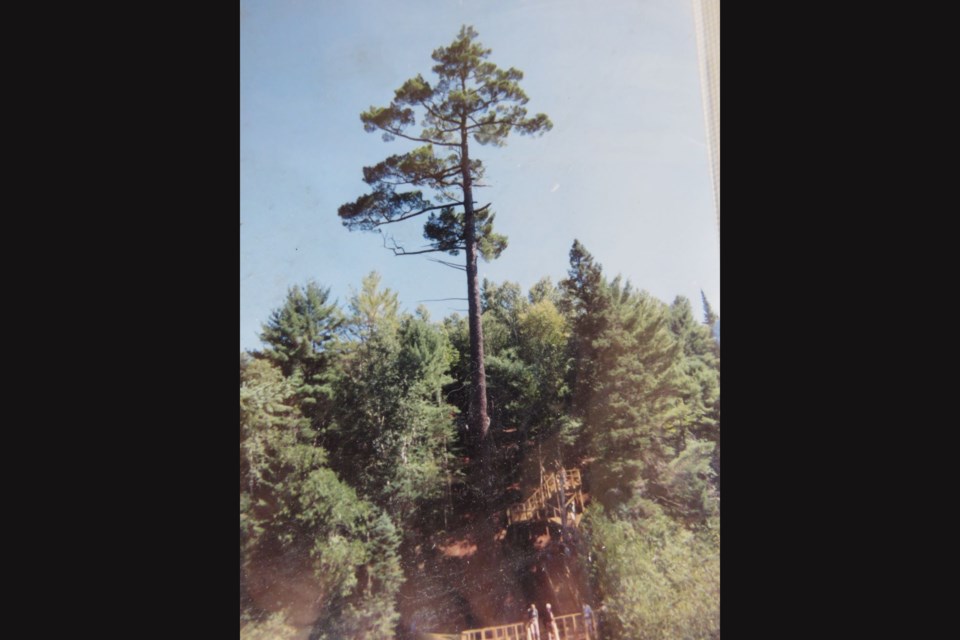

The Pinus strobus, or the eastern white pine, is Eastern Canada’s tallest tree. Before we took to cutting them down, Ontario trees regularly grew to 140 feet, with the giants scraping the sky at 160 feet or more. The Thessalon Pine, sometimes called the Kirkwood Pine, was a 162-foot behemoth, the tallest in the province.

Grant King, a local resident and speckled trout fisherman, located the tree in 1956. Thessalon-area historian Jim MacDonald brought it to the Ministry of Natural Resources’ attention in 1979. The ministry spent $45,000 in 1991 for steps and viewing platforms.

At its peak, it stood as high as a 15-storey building and was almost five feet across. From below, you would not see a branch until about 80 feet up. In the 1800s, this would have been considered prime timber—coveted by British shipbuilders for masts. Eventually, logging took over, but its location in a narrow valley with a meandering stream helped it survive the cut. Upon Confederation in 1867, the tree was already 225 years old.

Foresters’ reflections

Some people intimately know this tree through their vocation.

Brian Fox was a Unit/Area Forester with the Ministry of Natural Resources for about 22 years in Gogama (78-80), Wawa (80-87), Blind River (87-97) and Kirkland Lake (97-99).

He was a Regional Forest Health and Silvicultural Specialist in Timmins for 12 years (99-11). He retired in 2011 and now lives in Waterloo.

He described how he was first introduced to the Kirkwood Giant Pine in 1987 by Keith Hoback and Brad Eagleson at the MNR field office in Little Rapids.

“There was already an old makeshift set of steps leading down to the tree at the time," he said. "Every year, the fourth-year class of Lakehead University Forestry program would come down all the way from Thunder Bay to hold a one-week field camp on the Kirkwood Forest.”

One of the projects undertaken at the field camp was to find the age of this tree.

“As a class project, a large increment borer was used to drill into the tree near the base, and this enabled students to count 350 rings before hitting rot in the centre. Hence, they estimated that the tree was about 400 years old. They also measured the height with instruments.”

His reflections are a 'treet.'

“When I first saw the tree, I was blown away by its massive size, both in height and diameter," he said.

"It was so tall that you couldn’t really see the top until you were at least 100 feet away across the other side of the creek. This majestic tree captured my imagination, and I thought it would be great if more people could have the opportunity to see this treasure.”

In 1990, Sault Ste. Marie area was given the Forestry Capital of Canada national award. The Kirkwood Forest was given the Ontario Forest of the Year Provincial award as well.

“It was an exciting time and a great opportunity to showcase the area. We were able to develop the Giant Pine Site with a full set of stairs, viewing platforms and a bridge across the creek," Fox said.

The MNR promoted the new Kirkwood tour route with highway signs and brochures.

“More than 7,000 people visited the Giant Pine and signed the guest book per year. They came from all over North America and other countries as far away as Israel and Australia and left great comments in the book.

“I left Blind River in 1997. Those were the best 10 years of my career! Just before I moved, I noticed two small cracks at the base of the Giant Pine and wondered how much longer the tree would last," he said. "Much to my regret, a year later, the tree blew down in a storm.

"They thought it was likely wind shear with a severe down-draft that caused it to finally come down. You could also see the evidence of the wind shear in the plantations on the flats above the tree.”

What about “When a tree falls…?”

“I sure did hear and was saddened by the news of the loss of the tree. I had to see it for myself, so the next time I had a meeting in Sault Ste. Marie, I visited the site," Brian said.

"I still remember the moment when I stood beside the massive log. I was amazed at the amount of rot in the base of the tree," he added. "The decay went up the log farther than I had thought.

"I was reminded of the natural cycle of life and that all things pass away eventually."

There was an impact for Brian Fox.

“I did not regret having showcased the tree for seven years and was glad 50,000 + people got to enjoy it up close and be inspired by a true wonder of nature! Ever since my encounter with the Kirkwood Giant Pine, I have had a fascination with old growth trees and wanted to visit the giant Redwoods and Sequoias of California. I finally got to tour the incredible forests of California in 2017 and saw the 2000 + year-old trees that you could drive your car through!”

Visiting the fallen Ggiant

Mark Stabb is the Nature Conservancy of Canada's (NCC's) program director for Central Ontario – East

He also wanted to know, when a giant tree falls in the forest, does it make a giant sound?

He was there in 2015 and had this to say about his experience.

“One thing is for sure, when the Giant White Pine of Thessalon collapsed in 1997, it must have scared the heck out of local wildlife. And it would have been really shocking to any 'flying' squirrels that a moment before were mere red squirrels clinging to its branches.”

He said, “The Thessalon Pine survived the liquidation of the giant pines, even though it lived in the middle of a working forest. It was spared the axe, the crosscut saw, the chainsaw and then the mechanized cutters of today," he said..

"Growing at the bottom of a steep-sided creek valley, it would have been impossible to haul out in the days of horse-logging. The valley may also have given it refuge from fires and storms.”

In the end, it was the foresters, along with other community members, who saved the Thessalon Pine and turned it into a tourist attraction.

“In the 1990s, thousands of visitors came to marvel at this wonder of nature, and experienced interpretive signs, guided tours and spinoff information sites in the surrounding Kirkwood forest. I’m sure many a Thessalon resident remembers giving directions to city slickers looking to find the tree.”

Mark never did get to see the Thessalon Pine in its heyday, but a decade ago, he made his own pilgrimage to see the fallen giant.

“With an old pamphlet in hand, I turned off the Trans-Canada and headed up the highway north of Thessalon. A decaying roadside sign about the pine directed me up the nearby dirt road, but to no avail.

“After several dead ends and close calls with logging trucks, I went back to town to ask for help. I should have done that earlier.

"The first person I spoke with, the owner of a local general store, sang the praises of the pine and lamented its loss. He vividly recalled the days when busloads of tourists stopped (and shopped) before taking the 20+-kilometre drive north to visit the tree."

Armed with detailed directions, he eventually reached a clearing piled high with logs, likely the entrance to the site.

“Realizing that this log landing had a fine granular limestone base, I knew I’d found the old parking lot! Walking around the perimeter, I found the trailhead and followed a narrow gravel path to a creek valley. And there it was: the longest log on the ground in Ontario.

“Skeleton bits of boardwalk still remained, and there was a gap in the log where tree 'cookies' had been cut out for museum displays. But the final resting place was mostly natural and serene, with the giant lying peacefully alongside the creek that had nurtured it for three and a half centuries.

“I climbed on top, walked its length and sat down to commune with the tree for a bit," he said.

"I noted how it helped shade the brook and where small mammals left droppings along the stem.

"Walking back, I accidentally dislodged a toboggan-sized piece of loose bark," he said. "The exposed wood was covered with fungi, mosses, shavings from insect diggings, plus a metre-long skin of an eastern gartersnake. The snake, itself a big specimen, must have used the gap beneath the bark to help it disrobe when it came time to shed."

He also said he still feels a bit guilty about damaging the relic tree.

“It helped remind me that the great pine has an afterlife. Trees are meant to die. And when they do, life goes on. They become food sources, nesting spots, boomtowns for fungi and microbes and, yes, places where snakes go to strip.”

Understanding white pine growth

Fred Pinto knows a great deal about white pine and weevils.

He is a Registered Professional Forester and was the executive director and registrar of the Ontario Professional Foresters Association. Before this, Fred worked for more than 30 years with the MNR in various capacities, including the development of guidance for professional foresters in developing harvest and regeneration practices for a variety of forest ecosystems, including those with white pine.

He had seen the Kirkwood pine vertically.

When asked if trees put on girth over height as they age, he said it's not straightforward.

“Short answer: Trees are unable to move like animals, so to ensure that they can withstand wind, ice, etc., they tend to change their structure and wood composition," Fred replied.

"Trees will increase their girth and produce different wood to withstand the buffeting wind. Also, the girth of trees is more related to how well they are able to access resources. So trees with wider girths tend to be open-grown.“

He explained, “White pine has certain adaptations that have evolved over time.

White pines are long-lived, possess crowns that grow high above the ground, develop thick bark as the trees age, have deep roots, produce cones/seeds periodically in large amounts, and can thrive in a wide range of climates and soils.

"Each of these characteristics explains some of the adaptations to natural disturbances, growth, and reproduction.

“All living organisms, including trees, eventually die," he said. "White pine has evolved to live a long time; however, this doesn't mean that all of them do. Just like humans, they have an age class distribution.”

This tree lived a long life.

Cultural, spiritual significance

Trees have spiritual and cultural significance, so I reached out to Dr. Jonathan Pitt.

He is an Indigenous person with Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee roots. He resides on the Nbisiing traditional territory of Nipissing First Nation in North Bay. Dr. Pitt has received multiple teaching awards during his career. He was a full-time faculty member in the Schulich School of Education.

“When I think of pine, my memory goes to Chief Shingwaukonse (Zhingwaakoons “Pine”) or Shingwauk (Zhingwaak) who was paramount in The Treaty of 1850, Robinson Huron Waawiindamaagewin."

He recommends reading more about Mica Bay for historical context.

Jonathan said white pine holds profound cultural significance in Anishinabek teachings, serving as a vital symbol of peace, unity, and resilience.

“This mitig (tree) is deeply intertwined with the spiritual and practical aspects of life for Anishinabek people, reflecting core values and understandings.

“The white pine is often referred to as the 'Tree of Peace' in various Indigenous cultures. The white pine is an evergreen and symbolizes peace that endures throughout the seasons."

As for cultural use, he explained, “In Anishinabek tradition, the white pine is not only a physical entity but also holds Spiritual significance. The sap from the tree is utilized for various purposes, including as an adhesive for canoe building and traditional dwellings. Its needles are used to make teas that are rich in Vitamin C and have medicinal properties, particularly for respiratory ailments.

“The white pine reminds us of our traditional teachings and connection to the land (Aki).

“Ecologically, white pine plays a significant foundational role in the ecology of the land by providing habitat for various species of wildlife, and we often learn the Sacred Seven Grandfather Teachings from the forest canopy, all things are interconnected. This ecological significance aligns with Anishinabek core beliefs about stewardship of the land and responsibility towards All Our Relations.”

This tree alone had stature in a beloved community.

Other pines

Members of The Group of Seven were inspired by these majestic pines.

Where can people go to see Ontario’s tallest living white pine tree and perhaps hear the sound of the wind whistling through their towering crowns?

You will see many stately trees that are 90-100 cm in diameter. Over one metre, you are looking at trees at an age of approximately 300 years or more. These are Ontario’s large trees.

You can measure the diameter at what is called “dbh” (diameter at breast height, 1.34 m) with a flexible tape. You can estimate the height through Google: “determining the height of a tree.”

By latitude, there are many large white pines from North Bay through to Sault Ste. Marie, and many are located in many provincial parks.

So, the largest/tallest now remaining seems to be the Arnprior-Gillies Grove tree. The second is the White Bear Forest tree (and Ontario’s largest red pine is there as well) near Temagami, and a third is in Marten River Provincial Park. See the map for the Kirkwood Giant (+46.46161N -83.57346W) and the other big pines for directions.

Location is important. Send me the location of any big trees you find, maybe with a photo, and they can be added to the map. For comparison, the tallest tree in Arnprior is 47m with a dbh of 1.34 m. The Kirkwood tree was 49.4 in height with a dbh of 1.4 m.

You can pay homage to others, the hug will do it.

More information

You will be on the hunt for giant white pines.

To see the exhibit and tree cookie on the Thessalon-Kirkwood giant, visit the Heritage Park Museum – Little River – north on Hwy. 129. It will be open this summer.

Then, head over to nearby Little Rapids General Store, established in 1890. Much like its name, the store offers a little bit of everything, from livestock feed to over 30 different flavours of cheese. This stop is also well known to carry Penokean Hills Farms food products and some of the best summer sausages you will ever have. Drive north on Little Rapids Rd. into the Kirkwood Forest, and you will find the three-plaque stone monument commemorating the forest. You are then not too far from where the giant resided.

Backwards chronology

So on snowshoes a couple of weeks back, I stopped to embrace a very large white pine, and I remembered that day, five years back, that I searched for the Kirkwood Giant and realized the story was never completed!

Upstairs at the Canadian Ecology Centre, I stopped to look at our tree cookie from this tree and the poster donated at the time by the MNR. I have passed the exhibit every day for 26 years. I feel I know this tree.

That 2020 day was one of best examples of a “slog” - bushwhacking initiated for a good reason. It was tiring. It was one of the first escapades I enjoyed with new friends Liz Mulholland and Brian Emblim of Timmins, a relationship that has blossomed through many other adventures. You can still see the heavily plated bark as it continues its journey to nature.

My first story with Village Media was on June 3, 2020, and it was about the three crosses of Mattawa.

The banner said, “In this inaugural edition of Back Roads Bill Steer's new northern Ontario travel column, he examines four different versions of the story of the crosses' origin.” I had switched digital newspaper chains and found a new home for my avocation. This story – slated for thereabouts - was misplaced for a bit, hundreds of stories later.

It is said that, "if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?" is a philosophical thought experiment that raises questions regarding observation and perception.

Trees are important to us, including our spiritual side.

It lived a good life.

Even when big white pines become horizontal, they are still something to behold. Maybe all this prose is for its natural epitaph or obituary. I'm glad there were some eulogies.

Whew…finally fulfilled, now that this story about a special conifer has been shared on the back roads.