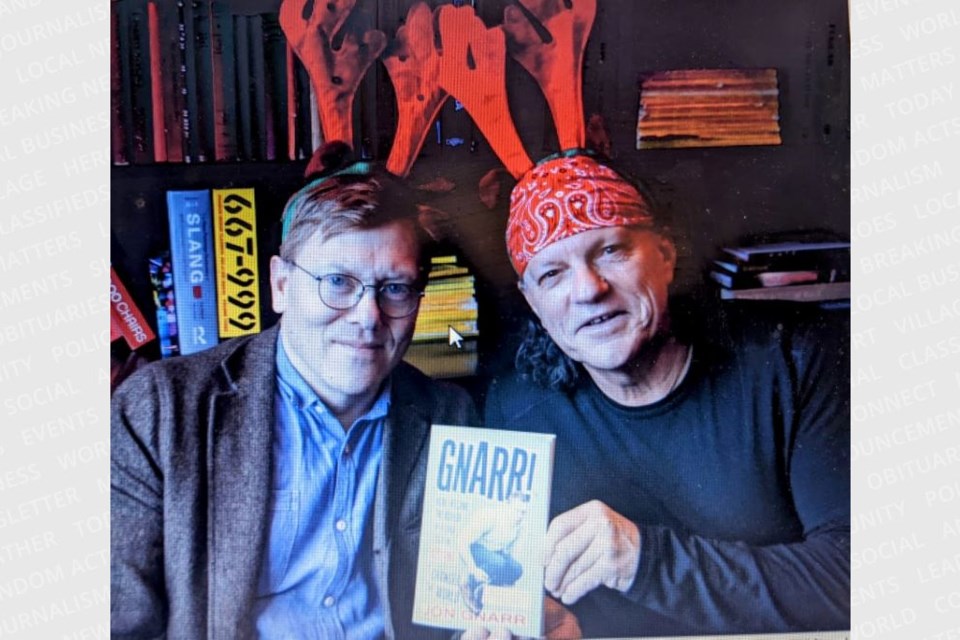

Among the many interviews I have engaged in since 1988 one stands out as particularly unique and interesting.

“Bill, who is the most famous person you have interviewed?” was a recent question to me and it brought me back to that interview.

The interview took place during a backroads trip to Iceland.

Through his publisher in New York, I made contact with the subject of that interview, a famous politician like no other at the time. Jón Gnarr.

He is one of two well-known Icelanders, Björk is the other. Gnarr knows her well and has worked on several projects with the singer, songwriter and composer.

Politics

It’s hard for politicians to have fun and be funny.

Jón Gnarr (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈjouːn ˈknar]) is the exception.

The comedic, former Mayor of Reykjavik may be more well-known than the volcanic eruptions in the region. He is best described as a political satirist somthing like CBC’s Rick Mercer and he is a politician like no other.

I interviewed him outside the city centre hostel located on snow-covered volcanic mountains. It started with, “the Vikings got the names mixed up,” about Greenland and his native land.

“I told a visiting journalist once this was nearby Greenland,” he added.

2016

“There are a few ways to get famous in Iceland,” says Gnarr. “Most of which revolve around the whimsical Icelandic character, personified to the rest of the world by Björk.”

The other he says, “Is to be 'flexible' to sudden changes of fortune (it’s probably a weather thing).”

In 2010, Gnarr, a stand-up comic, put his name forward for Mayor of Reykjavik.

Iceland has a population of 372,00, sixty per cent live in the capital city so the mayor is a prominent government figure.

Entering the race for mayor Gnarr promised to get the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park into downtown parks, provide free towels at public swimming pools, and a drug-free Parliament by 2020. He pledged a polar bear display for the zoo. and he swore he’d break all his campaign promises. The campaign started as a joke but he didn’t write the punchline.

It was a satirical gesture, designed to protest against the political class blamed for miring Iceland in the financial crisis. To his horror, and to that of the establishment, he won.

“Why do I always have to get myself into trouble?” he said, recalling his thoughts on the night of his victory.

And just like that, a man whose previous foreign relations experience consisted of a radio show (in which he regularly crank-called the White House and police stations in New York to see if they had found his lost wallet) was soon meeting international leaders and being taken seriously as the mayor of a European capital.

At the time he has been lionized as “the world’s coolest mayor” by his fans, who include Noam Chomsky and Lady Gaga (“I love the mayor of Iceland,” she once Tweeted).

It should have been a disaster. Gnarr had no background in politics. While campaigning, he ran into Hanna Birna Kristjánsdóttir, the incumbent mayor, backstage on a talk show and had no idea who she was. The Best Party logo was a parody – a clip-art picture of a thumbs-up.

“We chose the ugliest typography and most hideous colour combinations,” Gnarr writes in the book, all designed to ridicule professional politics. “After turning in a disastrous TV debate performance, Gnarr assumed the jig was up.” But his poll numbers just kept climbing.

In the economic depression aftermath of the country’s financial collapse of 2008/09 the Best Party emerged as the biggest winner in Reykjavik’s elections.

To the amazement of all he knuckled down and started doing the job. First things first: to break some promises. He had flippantly offered “free towels in all public swimming pools” on the campaign trail – that went out the window. “Ja, I had to raise everything that could be raised: all service fees; and no free towels – in fact, double the price.”

He merged schools to cut education costs. He laid off public sector workers:

“It was really hard," he said. "A difficult and not a popular political thing, but everybody knew it had to be done.”

One of his first official acts was to introduce "Hello Day." Reykjavík's residents were expected to greet each other as cheerfully as possible.

Soon afterwards Gnarr raised electricity prices in the city and laid off 60 people at the municipal energy company. The mayor cancelled subsidies for children attending music schools and raised taxes to cover his budget. During four his four-year term polls named Gnarr the "most honourable politician" in the country, and felt that he had the "most charm" and was more down-to-earth than any other politician.

He was the anarchist comedian elected on a promise to break his election promises. Four years of service, he was a punk rock mayor who dressed in drag, gave Yoko Ono honourary citizenship and entertained 95,000 Facebook followers with mayoral selfies and YouTube links. He was the high-school dropout who snuck into the halls of power, vowing to shake up the establishment and he did.

Background

Gnarr, for all his levity, knew how to assert himself. He came from a tough background. His mother was an alcoholic, his father the product of a violent upbringing, who had no time nor tenderness to spare for his son.

At school, the young Gnarr was written off as a troublemaker with no prospects. He remembers making his first joke in class, at the age of eight. (It was a play on words centring on the fact that, in Icelandic, the term for “bear cub” is similar to doorknob.) It brought the house down among students, but Gnarr was dismissed by teachers, “who said, bluntly, I was just plain stupid.”

His childhood was difficult, marked by bullying, psychiatry appointments, learning disabilities and an utter disinterest in school. At the age of 14, and for reasons he has never gotten to the bottom of, Gnarr was sent to a remote facility in northwest Iceland, for unruly teenagers.

“It was not a school," he said. "There were bars on the windows and you were locked in. I was there for two and a half years.”

He dropped out of high school after discovering the world of punk, which became an alternate education that introduced him to the subjects that shape his views even today: anarchism, surrealism and philosophy.

Since leaving office, Gnarr has dissolved the Best Party, which in any case, he says, “was only ever supposed to be an idea rather than a functioning reality. It wasn’t built to last."

He has no idea what he’ll do next. He will be starring in an Icelandic TV series called The Mayor and is considering running for president.

“If I do I will continue to improve the Icelandic way of life.”

Recently, a petition calling on Gnarr to stand for the highest office in the land was initiated.

‘Gnarr!’ How I Became the Mayor of a Large City in Iceland and Changed the World is published by Melville House (Penguin Random House Canada.) If you like Steve Martin’s Cruel Shoes, you will enjoy the admirable candour of Gnarr's memoir. It is a collection of offbeat, mostly humorous essays and short stories “of how it all happened.” See his Facebook page and YouTube interviews.

Because of the book and his stint as a politician, he travels a great deal, “But nowadays when I’m somewhere and being asked where I’m from and I say Iceland, and people say ‘Ah! Björk.’”

At the end of the Christmas time interview, he had sage advice for Back Roads Bill's daughter Ali.

“Don’t visit the Icelandic Penis Museum,” (so we didn’t; it is probably the only museum in the world to contain a collection of phallic specimens belonging to all the various types of mammals found in a single country.)

He also said, “Don’t put ice cubes in your drinks; it is too cold here anyway.” And he said satirically, “Don’t have a hot dog or line up for ice cream.” Icelandic people love these treats and queue up throughout the winter for both. Although visitors talk about volcanoes, “we don’t, it is like other natural disasters, and we are constantly aware what can happen like Eldfell,” on the Vestmannaeyjar - Westman Islands, (there will be a story about this eruption, forthcoming).

"Why can’t a politician have fun?" I asked him.

“They are insecure because they have learned to play a certain role and this does not fit in that role. On the other hand, they have opponents or the media that follow them closely and will try and scrutinize them at any given chance. So often, they’ve learned to walk through a minefield. They’re always careful — and when you’re careful it’s hard to have fun.”

While the Mayor of Reykjavik and visiting Toronto in 2014 he turned down the welcoming privileges for a visiting dignitary through Mayor Rob Ford’s office.

"And what did you think of him?" I asked Gnarr.

“He’s not a funny guy,” he said. “I think he’s one of the consequences of democracy.”

Now

Some years have passed but during the initial interview he said he thought Donald Trump was “outrageous and dangerous.” He feels the same now.

Gnarr remains active as a writer and comedian in his home country which he calls “the rock.”

Most recently he taught a screenwriting class at the University of Houston and spoke out on creativity and climate change.

At first, he said, “It seemed like climate change would be good for Iceland. It would be warmer, right?” He realized it wasn’t so simple. Ocean acidification will have implications for Iceland’s fishing industry. On a personal level, the countryside he remembers as a barren, treeless place 40 years ago now is thickly wooded, a change that has come so quickly the birds haven’t yet realized the fruit on apple trees is edible.

In passing Gimli, Manitoba, is home to the largest Icelandic community outside Iceland.

Gnarr is funny, have a listen to this three-part All Things Iceland podcast. Some funny words to listen to as you make your way, this spring, onto the back roads of Northern Ontario.