About 15 years ago a three-year old girl called in on the 9-1-1 emergency line in Sault Ste. Marie.

The girl's father had a seizure and thankfully he had just taught her to dial 9-1-1 using the television remote the day before.

The call came in to Joan Wyatt, the on-shift ambulance communication officer, or 9-1-1 operator, at the Sault Central Ambulance Communication Centre (SCACC).

Wyatt was able to coach the girl to first get her baby sibling off the couch into a safe position, and then helped the ambulance locate the family by asking the toddler if the ambulance sirens were getting louder or quieter as they drove around her area.

The father was saved and after he recovered he brought the daughter in to meet Wyatt and the paramedics that worked with her to save his life.

April 9-15 was National Public Safety Telecommunicators Week and in honor of that SooToday went to SCACC to hear about what some of our local 9-1-1 operators go through.

From food trays to phone calls

Wyatt has been a 911 operator in Sault Ste. Marie since 1980.

“My brother likes to tell people that I took the call when Mary when into labour with Jesus,” said Wyatt, the most senior ambulance communication officer, or 9-1-1 operator, in the city.

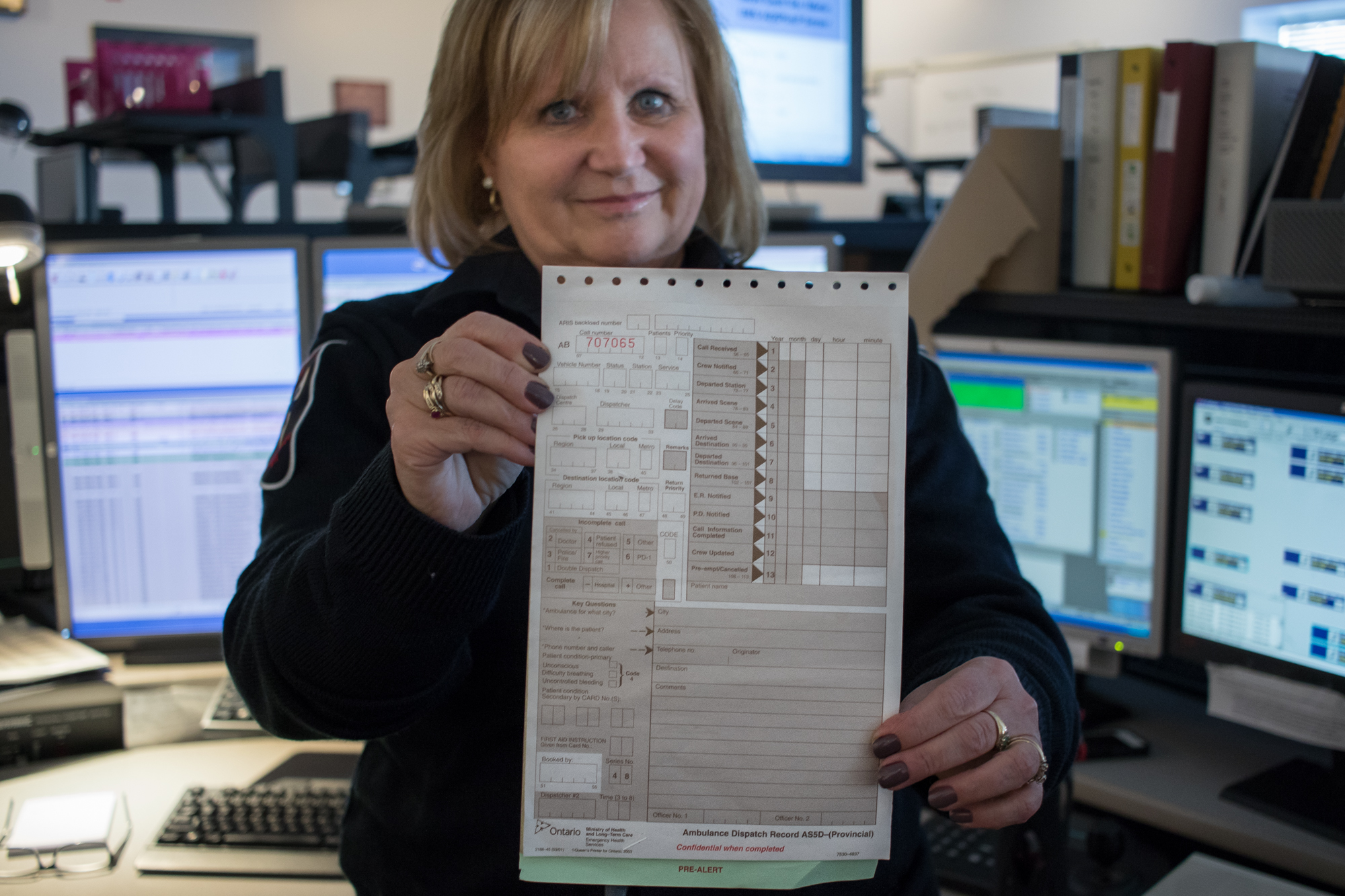

37-year public safety telecommunicator veteran Joan Wyatt shows off a paper dispatch form of the type she had to use back when she started in 1980. Now everything is done on computers. Jeff Klassen/SooToday

37-year public safety telecommunicator veteran Joan Wyatt shows off a paper dispatch form of the type she had to use back when she started in 1980. Now everything is done on computers. Jeff Klassen/SooTodayWhen someone dials 9-1-1 in-town, the call first goes to a switchboard operator who asks 'Do you need police, fire, or ambulance?'

If a person requires an ambulance the calls go to SCACC, which covers a 75,000-square-km area surrounding Sault Ste. Marie - from as far east as Serpent River and Elliot Lake, and as far north and west as White River and Hornepayne.

Last year, the centre dispatched 24,640 calls.

When she first started she was working at the cafeteria in the hospital but hated it and some paramedics that ate there suggested she get certified as a radio operator and in first aid so she could apply.

“For most people I think that’s what it is - you fall into this by accident. I don’t think anyone ever grows up and says they want to answer the phone to screaming hysterical people for the rest of their life,” she said.

Throughout her 37-year career, Wyatt’s seen it all.

Wyatt remembers her first shift back after her maternity leave when she had her daughter - she received an emergency call for a ‘crib death’.

“That night I must have called my husband 500 times getting him to check the baby. Those are the calls you don’t forget, everyone has them,” she said.

Some calls, although of course serious, can be quite funny in retrospect, like a call Wyatt’s coworker Brad McClelland received after a child swallowed a handful of pocket change.

“The dad wouldn’t listen to first aid instruction and kept hitting him on the back. Every now and then you’d hear ‘there’s a nickel’, ‘there’s a dime’, ‘now a quarter’, until it was all out,” he said.

A big responsibility

The types of emergency situations that 911 operators find themselves dispatching for mean that they are held to high standard of conduct and if they make even a small mistake they can face big consequences.

In the early 1980s, Wyatt was subpoenaed to testify in a case where a woman had been assaulted and had then dialled 9-1-1 and passed out during the call.

Wyatt’s in-court testimony was used to corroborate the story of the victim.

Her manager at the time told her it was the first case of an Ontario 9-1-1 operator having to testify in court regarding a call however the operators now say its something that is constantly looming over their day-to-day work.

They talk about one story where 9-1-1 operators in another area mistakenly thought that a man who slurred because of his diabetes was drunk and, because he was then perceived as a threat, paramedics waited to help him until police arrived for their safety and because of that extra delay, he suffered medical consequences.

The 9-1-1 operators in the story were held liable for their misdiagnosis.

Frequent flyers and magic words

In order to prevent them from making a major mistake, and possibly terminated or jailed, operators in 2017 are more scripted and structured in how they dispatch calls, however, their strict adherence to rules are sometimes taken advantage of by people looking to abuse services.

SCACC call them ‘frequent flyers’ – people who are not in an emergency medical situation but frequently call 9-1-1 so that ambulances will take them to the hospital for some non emergency reason - perhaps just for a warm meal - or even just to get a lift across town.

“Some just want a sandwich, some are lonely, others, we don’t know why they do it, there’s a lot of mental issues,” said Wyatt.Wyatt and other operators remember when the hospital was downtown there was one caller who would call up for an ambulance because they wanted to drink at the Eastgate Hotel and Algonquin Hotel down the street from the hospital.

When it gets to be a serious problem police or social services may get involved.

Some of these callers learn to bypass waiting for an ambulance by saying ‘magic words’ – making up key symptoms like “shortness of breath” or “chest pains” that force ambulances to put them at the top of a priority list.

Other ‘frequent flyers’ are those that need to go to the hospital but think that if an ambulance takes them there they don’t have to wait in line – a fallacy that not only doesn’t lead to faster service but ties up emergency services for those who actually need it.

Trying to manage in mostly forest

911 operators aim to have a vehicle dispatched out the door in two minutes or less, something not always easy to do when it’s hard to locate a person.

If the person doesn’t know where they are, and if they aren’t on a land line, locating them gets exponentially more difficult.

When its really vague they start asking the distressed person to try and give them nearby landmarks, recall the last thing they’ve seen, and the operators will scour online directories and maps using whatever information they can.

Locally, the operators cover one of the biggest dispatch regions in Canada - 75,000 square km of mostly forested land.

Even when they can locate someone in that large, mostly-undeveloped region, there is still the hurdle of getting the person to the hospital.

SCACC staff retrieved people by dispatching planes, helicopters, ATVs, snowmobiles, and even trains.

One evening a call came in by satellite phone of a man complaining of chest pains.

The only problem is that he was on a boat in the middle of a lake near Franz, about 50 km north of Wawa, far away from any roads.

The SCACC operators who took the call contacted a major train operator that went through that region and asked if they could perform an unscheduled stop in the middle of the bush to pick the man up, which they did, and managed to get him from the middle of nowhere to White River, and via ambulance to a hospital in Wawa by 5 a.m.

Disturbing new trends

In recent years, the ambulance operators in the Sault have noticed a disturbing growing problem – calls related to fentanyl overdoses.

As soon as the SCACC operators started giving CPR instructions over the phone, they would hear a ruckus on the phone and it turned out the unconscious person had woken up and started swinging their arms around violently.SCACC operators say it started maybe five to seven years ago; people would call 9-1-1 reporting that someone had died because they were blue-skinned and out cold.

“After a while it was like, wait a minute, what’s going on here? With the overdoses, it turns out, as soon as they jostle them it shocks the respiratory system and they come around,” said Wyatt.

Supporting each other

Because of the high stress levels the types of calls they take generate, SCACC staff form tight bonds –marked by what they call lots of in-group ‘black humour' - and always lend each a shoulder to cry on and outlets to vent so that they don’t bring the stress home to their families.

“If we have a rough night we might talk it out over a beer. We have each other, and the black humour, that’s how we cope. We say stupid things, and curse like truckers - rude and crude,” said operator Paula Hiller.

“We couldn’t stay doing this for as many years as we have if we didn’t,” said Wyatt.

Recently local emergency services groups have started a new peer support program to help police, ambulance, fire, and emergency telecommunicators deal with the mental stresses they encounter.

As part of this, Wyatt was recently trained to be able to give mental health support and connect her co-workers with mental health resources when needed.

“We hear about things in here that the public doesn’t know about. (We know that) when a news story comes out it’s not the whole story – if a person is beaten, or murdered, or child rape, (911 operators) hear about that stuff. Not everyone can do this job,” said Wyatt.

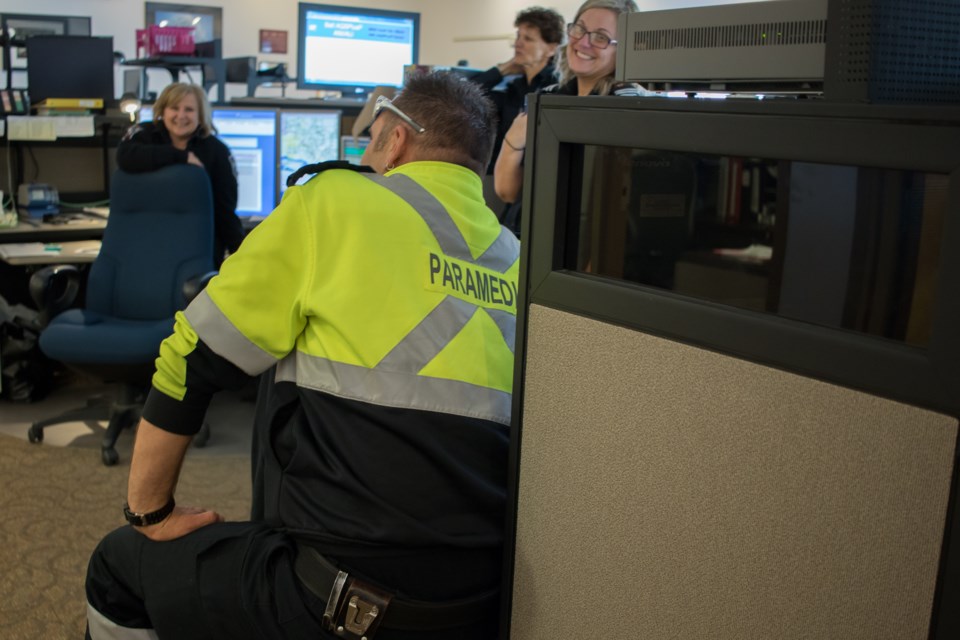

Some of the full-time ambulance communication officers at Sault Central Ambulance Communication Centre. (From left) Brad McClelland, Joan Wyatt (front), Marion Beaulieu (back), Paula Hiller, and Tammy Ryan. Jeff Klassen/SooToday

Some of the full-time ambulance communication officers at Sault Central Ambulance Communication Centre. (From left) Brad McClelland, Joan Wyatt (front), Marion Beaulieu (back), Paula Hiller, and Tammy Ryan. Jeff Klassen/SooToday