One 68-year-old man was in the hospital for four years, hooked up to a feeding tube, breathing tube and a ventilator.

An 82-year-old man required dialysis, a feeding tube and a mechanical lift to get out of bed.

Another patient had a bed sore down to the muscle and couldn't move his arms or legs.

All of them were "alternate level of care" (ALC) patients, meaning the hospital believes they should no longer be there — and if they or their loved ones disagree, they could be fined for refusing to move.

Internal hospital documents obtained by The Trillium illustrate the complex needs of these patients, who sometimes can't afford private care, have no family to look after them and medical issues advocates say are too severe for long-term care.

Hospitals give patients an ALC designation when they deem them to no longer require acute care. An ALC patient with intense needs will require complex care for the rest of their life. Someone with fewer needs may be a fit for a long-term care home or home care. Retirement homes, which don't require nurses on staff, are often good spots for seniors who are still somewhat independent.

The problem, seniors' advocates say, is that hospitals, facing funding pressures from the province, have too few complex-care beds, meaning high-needs patients linger indefinitely in acute care — while the hospitals employ intense pressure to get them to leave, often to an inappropriate care setting.

A major part of the Ford government's solution has been Bill 7, a law passed in 2022 allowing hospitals to fine ALC patients who refuse to go to long-term care homes.

Premier Doug Ford said in 2022 that Bill 7 was "absolutely necessary" because "there are 6,000 beds being taken up by alternative-level-of-care patients in hospitals ... the highest number in the history of this country."

In 2017, before she was the minister of health, Sylvia Jones called them "bed blockers," a term advocates say is derogatory.

"Do you know why we call them bed blockers? Because they need to be served and assisted in some other form of health care. Many times it’s long-term care," she said.

The Ford government said its strategy has helped transfer over 30,000 people to long-term care.

“Bill 7 ensures people across the province receive the care they need, in a setting that is right for them," Jones' spokesperson, Hannah Jensen, said in a statement. "It frees up hospital beds so that people waiting for surgeries can get them sooner, eases pressures on crowded emergency departments, and follows the lead of many other provinces, which have had similar policies in place for decades."

Designating a patient ALC "is exclusively a clinical decision made by a patient’s attending physician who has determined that a patient’s care needs are no longer met in a hospital," she added.

Many ALC patients can't go home

The Trillium obtained weekly ALC patient notes for three hospital sites run by Trillium Health Partners (no relation to this news outlet): the Mississauga Hospital, Credit Valley Hospital, and Queensway Health Centre, as well as its inpatient rehabilitation facility, the Reactivation Care Centre.

The documents, which cover from the beginning of January to the end of March last year, were compiled by Trillium Health Partners as part of the recently struck-down Charter challenge of Bill 7.

Many ALC patients were managing just fine on their own, but then had a sudden injury, like a stroke or a fall.

At their age, their injuries are often long-lasting or permanent, and the patients now require complex, ongoing care. Some have feeding or breathing tubes. Others require mechanical lifts to get into wheelchairs. Many are severely cognitively impaired.

Their families are unable to care for them, and retirement homes are too expensive and often don't provide the right type of care. Long-term care homes require a co-payment, and getting a rate reduction isn't guaranteed.

In several cases outlined in the hospital notes, other medical centres rejected a transfer, saying they couldn't care for the patients either.

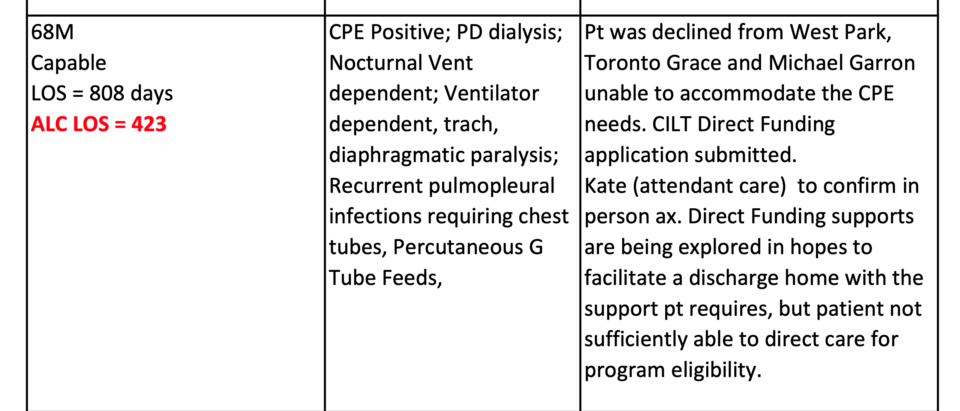

One patient was in the hospital for more than three years — more than a year as an ALC patient. The 68-year-old man had a paralyzed diaphragm and recurring infections in the area between the lungs and the chest wall. He was on dialysis, needed a nocturnal vent, a breathing tube, chest tubes and a feeding tube.

He was rejected from rehab hospital West Park Healthcare Centre, complex continuing care hospital Toronto Grace Health Centre, and Michael Garron Hospital.

Credit Valley Hospital's notes said it was exploring ways to discharge the man home, with in-home care.

"I don't know if you've ever seen what you have to do to take care of somebody who's on a trach (breathing tube). You have to stick tubes down into their trach, and suction out their lungs and stuff. And they're expecting families (to do that)," said Jane Meadus, a lawyer with the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly.

Another 82-year-old man who was "mostly confused" was on dialysis and had a feeding tube, which his wife was "unable to manage ... on her own." The hospital wrote that it planned to submit a long-term care application. He was an ALC patient for at least four months.

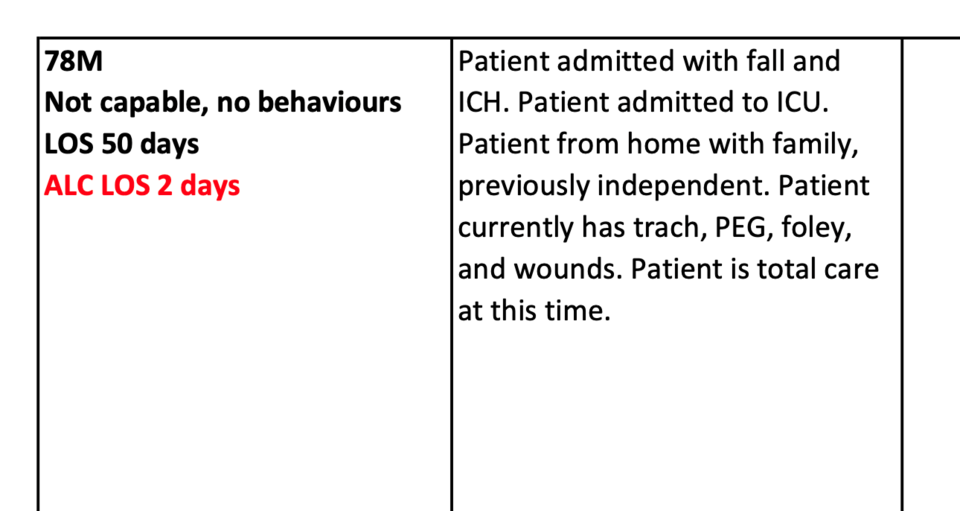

A 78-year-old man who was "previously independent" had a fall and a subsequent stroke. He was deemed ALC after ending up with a breathing tube, feeding tube, catheter and non-specific wounds.

In a statement, Trillium Health Partners said it's facing "extraordinary demand for health care — caring for a record-high number of patients during the respiratory illness season and more than ever in unconventional settings as patients wait for a bed."

Spokesperson Priyanka Nasta said a "significant number" of ALC patients are best served in long-term care, complex continuing care or home care.

"This designation is made in consultation with the patient as part of a thorough clinical assessment. In these cases, long-term care and home care are much more appropriate environments to support comfort, healing and recovery," Nasta said.

Others waiting for mental health care for months

Another group of patients in the documents shines a light on hospitals' struggles to find placements for younger patients who need mental health care. Some are described as "capable," but because there are no other supports available, they linger in hospital for months.

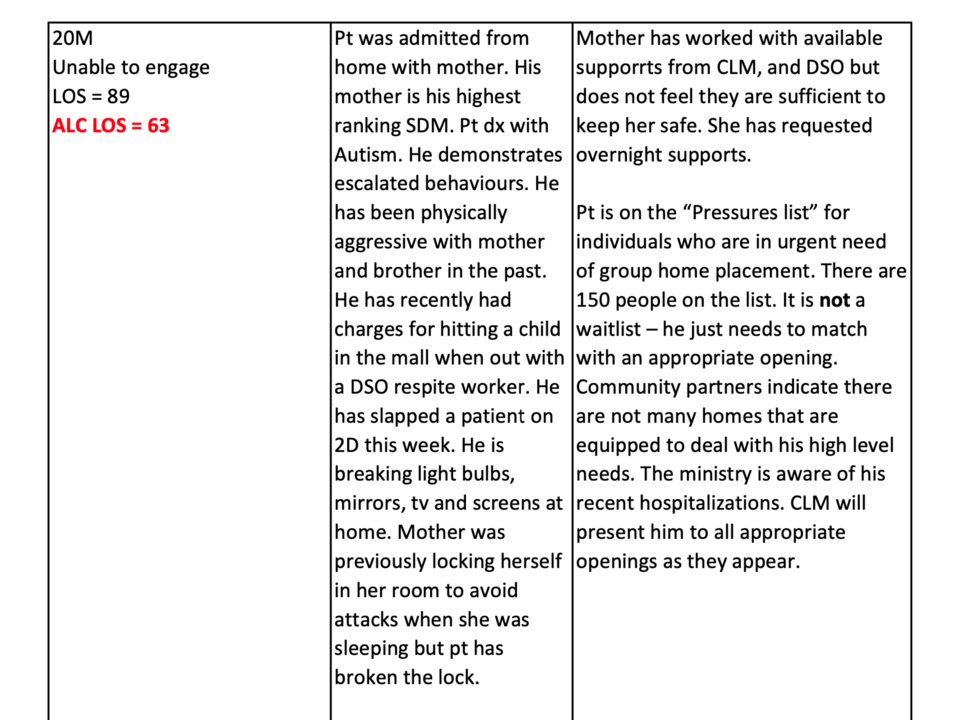

One 20-year-old man with autism was "physically aggressive" with his mother and other patients in the hospital. He broke light bulbs, mirrors and screens at home.

"Mother has worked with available supports from [Community Living Mississauga], and [Developmental Services Ontario] but does not feel they are sufficient to keep her safe," the hospital notes read.

The patient was in hospital for at least two months while he waited for placement in a group home.

"Community partners indicate there are not many homes that are equipped to deal with his high level needs," the hospital wrote.

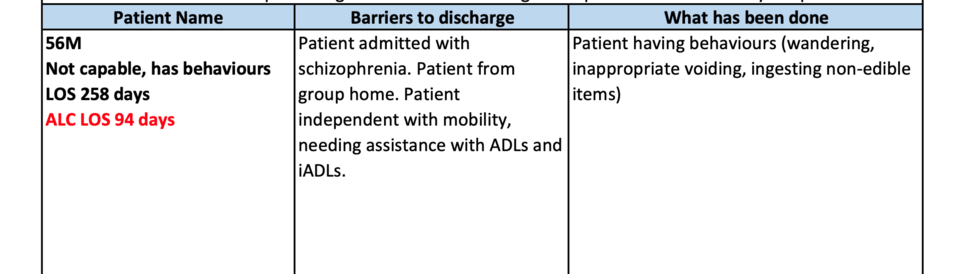

An "independent" 56-year-old man with schizophrenia but no physical health issues came from a group home. His behaviours included wandering, inappropriate urination and eating non-edible items, the hospital wrote. He was an ALC patient for at least three months.

A 38-year-old homeless woman had been living with friends but had "limited ... supports in the community." Her only issue was that she couldn't put weight on at least one limb. She was an ALC patient for at least 40 days.

'Immense' pressure from hospitals to discharge patients

For many ALC patients, it appears there is simply nowhere to go. But loved ones describe intense pressure campaigns from the hospitals to get them out.

"It doesn't matter where," said Natalie Mehra, the executive director of the Ontario Health Coalition.

NDP MPP Chris Glover's brother was one such patient. After he fell into a coma following a surgery, he had a feeding tube, a stage four bed sore — the most extreme type, exposing muscle, ligament or bone — and couldn't move his arms or legs, Glover said.

"Every bodily function he had needed to be tended to," he said.

The hospital, which Glover didn't name, told the family they had 10 days to take him home or find a long-term care home, or it would discharge him, Glover said. The pressure was "immense," he said.

"How do you discharge somebody — it's not like they're gonna put him in a taxi. Like, you can't do it. He's got a (feeding) tube. He's, at best, in a gurney," he said.

Glover said his brother lives in a different city and works long hours, and his parents, 87 and 91, couldn't care for him either. Glover said his family phoned several long-term care homes but none would take a patient with a feeding tube.

"What they were saying did not make sense. It just was not feasible," he said. "But my mother felt great stress because of these threats."

The pressure these patients face isn't just from the hospitals. Since the Ford government passed Bill 7, at least five ALC patients have been fined for refusing to leave hospitals. One woman was fined more than $28,000.

Glover said he was able to push back with the help of the Ontario Health Coalition.

"I have some understanding of the system, and I have people who can guide me, but so many other people in the province do not have that advantage," he said. "And I think about other people being pushed out of hospitals when the patients obviously need care, and that's just wrong."

Glover said his brother is recovering well — his bed sore has mostly healed and he's eating without the tube. He's now in a long-term care home, which is now the appropriate place — "but it just was not at that point," Glover said.

Trillium Health Partners said some complex health needs, like mobility challenges and feeding tubes, "can often be managed safely in community settings like long-term care or at home with the right support."

Patients with more intense needs require complex continuing care before they can return home or to long-term care, its spokesperson said, adding that the hospital network "has nearly 160 complex continuing care beds, which consistently operate at full capacity."

"Our doors are always open to care for people in their time of need and the transition to home or community is done with compassion and collaboration with our patients and their families," she said.

Hospitals best for many ALC patients: advocates

The problem of ALC patients in acute care beds is not insignificant.

In January 2023, there were 4,740 ALC patients in Ontario, and 72 per cent of those were in acute care. At the three hospitals in the documents, there were 12 patients in acute care beds waiting for long-term care that month. Fewer than half of ALC patients were waiting for long-term care at Trillium hospitals.

Last year, Health Minister Sylvia Jones' office said the number of ALC patients being discharged since Bill 7 passed in 2022 increased by 34 per cent, and the length of the average ALC stay has reached an all-time low — nearly half as long as it was in 2019.

Trillium Health Partners said it has to balance the needs of acutely ill patients with those "who are ready to be transitioned from hospital."

The hospital network "uses the framework laid out in Bill 7 to support safe transitions of care after all other options have been explored to ensure patients receive timely care in the most appropriate setting," Nasta said.

Transferring patients to community and home care has freed up the equivalent of two inpatient units since 2018, she said.

But advocates who work with these patients and their loved ones say the solution is more hospital capacity — not getting ALC patients out of hospitals, which are often the only places suited to provide the care they need.

"I've done this for 27 years, ever since the term ALC was created," Mehra, the Ontario Health Coalition's executive director, said. "The issue is, really, patients are being blamed for a lack of services, and Bill 7 is the most extreme legislative response to that."

Hospitals often misinform ALC patients' loved ones about the type of care retirement homes or even long-term care homes can provide, Mehra said. Retirement homes aren't medical facilities and aren't legally required to have a nurse on staff, she noted.

"A whole bunch of (these patients) need fairly complex levels of care," Mehra said.

"There's nowhere for them to go," she said. "That's the problem."

Meadus, with the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly, said the documents don't capture the full scope of the problem, since so many people leave hospital quietly.

"A lot of people aren't even allowed to apply for long-term care," she said. "They're just told they have to leave as soon as they're ALC."

Chronic care is supposed to be a destination, but hospitals are "getting out of that business," Meadus said.

"Long-term care won't take them. Complex care won't take care of them," she said. "So, where do they end up? They end up sitting in an acute care bed in a hospital."

Some of the people Meadus works with have been told by hospitals that they'll have to remortgage or sell their homes to pay for their family members' care, she said.

Even if they have money, patients shouldn't have to buy what should be available publicly, Meadus said.

"If you had cancer and your doctor said, 'Well, you're rich, so we won't provide the care for you here. You have to go to the United States and purchase it,' you'd be up in arms," she said.

Meadus said Ontario needs more complex-care beds, better access to rehab and more community supports, like home care and group homes, to prevent people from ending up in hospital in the first place.

"We need to make sure that all parts of the health system are robust enough," she said.