EDITOR’S NOTE: A version of this article originally appeared on The Trillium, a new Village Media website devoted to covering provincial politics at Queen’s Park.

Late last week, the province quietly unveiled the next step in its plan to get 1.5 million homes built by 2031.

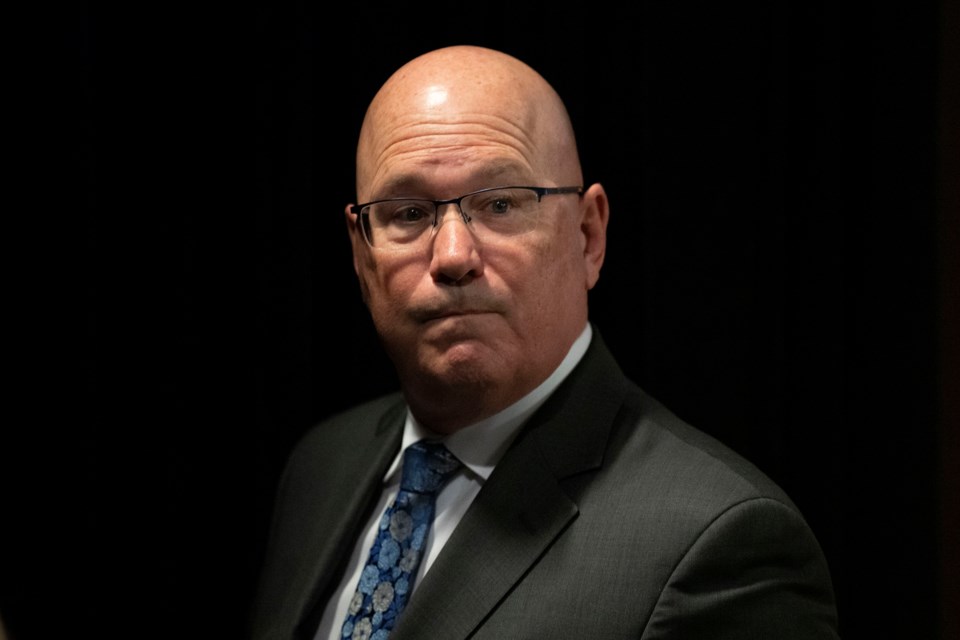

Housing and Municipal Affairs Minister Steve Clark asked 21 smaller municipalities to set a 2031 homebuilding target and develop a housing "pledge," essentially a strategy to get there.

The cities — which include Sault Ste. Marie — range in size from East Gwillimbury on the smaller end, with a population just under 35,000, to Greater Sudbury, with a population over 100,000.

It's similar to what the province did late last year, when it assigned 29 of the largest and fastest-growing cities 2031 housing targets.

What's different this time around is the smaller municipalities — those projected to have a population over 50,000 by 2031 — get to set their own targets, whereas the big cities had targets forced on them by Queen's Park.

"In recognition of the fact that more homes are needed in communities across Ontario — in addition to the 28 municipalities that have committed to their housing pledges — the province is welcoming locally appropriate housing targets and pledges from 21 other mid-sized and large municipalities throughout Ontario as part of the ongoing work to get 1.5 million homes built by 2031," said Victoria Podbielski, a spokesperson for Clark, in a statement to The Trillium.

Clark's latest plan was released to the public on June 30 but he sent the affected mayors a letter on June 16, obtained by The Trillium, asking them to set targets and pledges. It also came with some suggestions on what cities should consider when developing their plans for reaching the target.

They include encouraging "gentle intensification to enable and expedite additional residential units in existing residential areas," zoning reform "to permit a greater range of housing to be built without the need for costly and lengthy rezoning applications," whether developments are approved fast enough, if there's enough infrastructure to accommodate growth, and more.

"Our intention in requesting a housing pledge is that it will be approved by municipal councils and help codify council’s commitment to their target," she added.

Municipalities have until Dec. 15 to submit their targets and pledges to the province, Podbielski said, "but we have already seen some promising signs they are moving quickly on it."

A few town councils have directed staff to figure out an appropriate number and develop a plan. Aurora, Welland, Belleville, Sarnia and Peterborough have all gotten started on that work, representatives told The Trillium in interviews and email statements.

Welland's ahead, having already set a 2031 target of 12,257 units. Most of the work needed to develop its target and plans to meet the target was done last year when the city came out with its housing action plan, so staff were able to move quickly.

At least one mayor is happy the province is letting the smaller municipalities come up with their own targets, versus having them handed down.

"We're thankful for that," Aurora Mayor Tom Mrakas told The Trillium. "So that way, what we do come up with is appropriate for our community."

"My belief has always been that we need to do our part, but also we need to ensure that the growth that does occur within each of our own communities is appropriate," he said. "And we're not over-developing the communities, that's just as bad as under-developing."

Allowing these municipalities to set their own targets, versus having them assigned, could set the province up for some political trouble if the cities don't set ambitious enough targets, said David Amborski, a professor of planning at Toronto Metropolitan University.

"There may be some municipalities that don't want growth, and they'll try to keep their targets low. That's not going to be very helpful from a broader perspective, and that could be an issue," he said.

"But if a municipality truly wants to meet targets and look at affordability, then they set targets and they have something to measure against," he said.

It would be good to set the targets by housing type, such as highrise versus mid-rise, Amborski said.

"You should look at the types of housing you're trying to achieve because that's gonna help you look at the kind of community you want," he said.

If the province doesn't like a certain target, it can exert some "moral suasion" to get the targets more in line with what would be necessary to meet the province's overall target of 1.5 million homes by 2031, he said.

When Clark first announced the housing target plan last fall, Toronto and Ottawa — two of the 29 cities assigned targets — already had strong mayor powers. On June 16, Clark gave all the other mayors the same powers, save for Newmarket's John Taylor.

Those 28 mayors now have the power to set budgets, veto bylaws, and pass bylaws with just one-third of their council’s support — only if these bylaws deal with provincial priorities like getting more housing built. They'll also take charge of appointed senior civil servants in their municipalities.

Podbielski, Clark's spokesperson, wouldn't comment on whether the province is considering giving the mayors of the 21 cities included in the latest housing target initiative the same powers.

Mrakas said he hadn't considered it. Peterborough Mayor Jeff Leal, a cabinet minister under Kathleen Wynne, said he doesn't think he needs them.