EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared on The Trillium, a Village Media website devoted to covering provincial politics at Queen’s Park.

Principals at schools experiencing shortages of educational assistants were more likely to recommend students with special needs stay home, according to a new report from advocacy group People for Education.

About 72 per cent of elementary schools where principals reported daily shortages of educational assistants (EAs) recommended students with special needs to stay home, compared to 56 per cent of the schools where no daily shortages of educational assistants were reported, said the report, which was released on Monday. In high schools, 67 per cent of the schools experiencing shortages reported asking some students to stay home, compared to 53 per cent where educational assistants were regularly available.

Safety and the lack of necessary support were the top two reasons principals cited for recommending students remain at home.

The People for Education report was based on its annual school survey sent to principals at schools across the province, with 1,030 responses from 70 of 72 school boards, representing 21 per cent of the province's publicly funded schools.

More than 40 per cent of schools that responded to the survey — 42 per cent of elementary and 46 per cent of high schools — reported shortages of educational assistants each day, with many saying that this meant special education teachers were forced to fill the gaps.

"More EAs are needed. Our SERT (Special Education Resource Teacher) team is acting as EAs most of the day and cannot get to special education for those who are struggling academically," one elementary school principal in the Greater Toronto Area was quoted as saying in response to the survey.

"This is really a big problem and it sort of shows the consequence of staff shortages," said Annie Kidder, executive director of People for Education. "You might think it's a kind of theoretical issue, but when you see that connection, you go, this has a real clear, instant impact on kids with special needs because it's shocking to think that some kids can't actually go to school either because the supports aren't there or because the principals feel it's not safe."

Kidder said the bigger issue and question is whether the province has "really figured out all of our policy around special education" and the supports that are needed for students with special needs.

"How are we making sure that they are truly supported, and not just supported, but learning, thriving in school?" she said, adding that the EA shortage is the "canary in the coal mine."

"It's really clear, it's really concrete, and it's causing real problems, and it is surprising to see that significantly more principals are recommending that students stay home than had in the past," Kidder added.

Several groups, including unions, have raised concerns about staffing shortages in schools.

Last fall, the Ontario Principals’ Council said in response to a survey of its members that staffing shortages are "continuing to have a negative impact on student learning, safety and engagement.”

“Short-term solutions have not resolved the problem. This crisis must be addressed immediately, with long-term and sustainable solutions," the council said.

Earlier this year, teachers unions rejected the Ministry of Education’s request to support a temporary measure to increase the number of days retired teachers could work from 50 to 95 before their pension is affected, saying it's not a sustainable solution and doesn't help with retaining or attracting new educators.

Education Minister Stephen Lecce called the decision "regrettable" and said the government is looking at both short-term and long-term solutions to address staffing challenges.

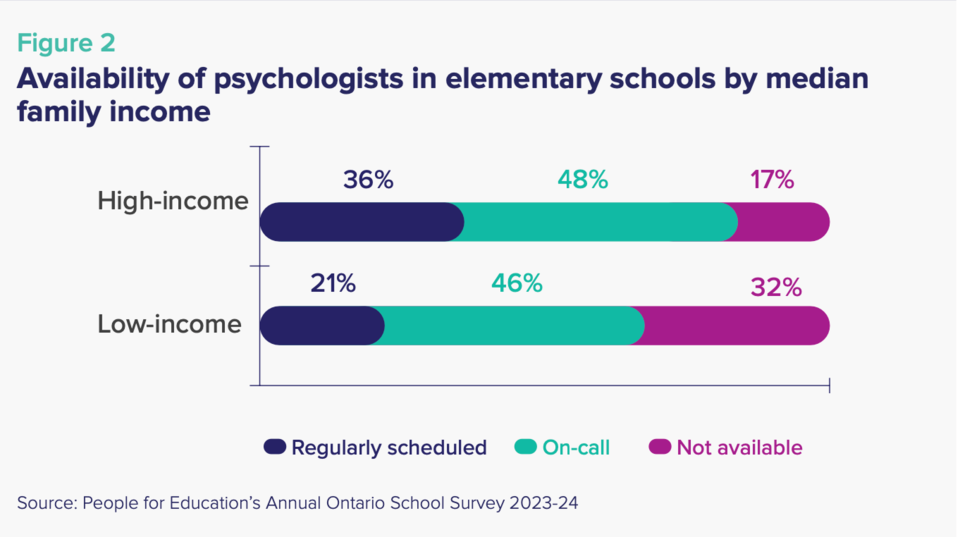

The People for Education report also examined differences in special education needs and schools' access to psychologists based on socioeconomic status. A higher proportion of students at elementary schools in low-income neighbourhoods needed special education supports compared to schools in high-income areas — 20 per cent versus 14 per cent, respectively.

There were also reported differences in accessing psychologists — just 21 per cent of elementary schools in low-income areas reported having access to regularly scheduled psychologists compared to 36 per cent of schools in high-income neighbourhoods, a finding Kidder said was really surprising.

"At the same time, low-income schools have more than double the proportion of students waiting for assessments," the report stated. "Assessments are important because once a student is assessed and identified with a special education exceptionality, they have a right to a range of special education supports."

"At the same time, low-income schools have more than double the proportion of students waiting for assessments," the report stated. "Assessments are important because once a student is assessed and identified with a special education exceptionality, they have a right to a range of special education supports."

The report did find, however, that low-income elementary schools were more likely than high-income schools — 90 per cent compared to 74 per cent — to have Individual Education Plans (IEPs) in place for students waiting for these assessments. An IEP is a written plan that outline services, special education programs or accommodations that will be provided for a student.

"What we're seeing are cracks ... and inequity, and both those things are worrying," said Kidder, though she said the fact that IEPs are still in place without assessments in some cases is a good thing.

"I think what this shows is that in those schools, the educators, the teachers, the principals are doing as much as they can to make sure that kids have their IEPs so that they're getting, hopefully, the supports and the accommodations that they need," she said.

Overall, this year's survey found an all-time low with 26 per cent of elementary schools saying they had regular access to psychologists and an increase from 13 per cent in 2016-17 to 24 per cent in 2023-24 of schools saying they had no access to psychologists.

In its report, People for Education called for the government to establish an education task force that would include teachers, principals, unions, school boards, special education groups, students and other stakeholders "to provide input on government policy before it is implemented, and to help design new policy and funding models to address a range of issues including staff shortages, and effective and equitable design for special education supports and programs."

In response to questions about the report, Isha Chaudhuri, Lecce's spokesperson, said the government is increasing special education funding for the upcoming school year by $117 million to $3.5 billion, and has added 9,000 more education staff, including 3,500 more EAs, since 2018 "to ensure students are learning and safe."

"Our government has invested $118 million in mental health resources for 2024-25, which represents a 577 per cent increase from 2018 under the previous Liberal government and hired more mental health and social workers to support children in need," she added. "This year alone, our government invested $250,000 to Ophea, to develop a training module to promote consistency in how provincial school boards train staff on supporting children with prevalent medical conditions.”