For many, the holiday season is synonymous with family gatherings, often requiring arduous and stressful travel. This is so much a part of our culture that getting to a place to be with loved ones has been the plot of many holiday movies — from Planes, Trains and Automobiles to the countless Hallmark Channel Christmas movies now available all year long.

In a time when many people are feeling lonely and isolated, celebrations with family and friends can feel like a lifeline. This is perhaps why many Canadians and Americans ignored recommended social distancing measures over their recent Thanksgiving holidays. In Canada, gatherings related to the October holiday resulted in a spike of COVID-19 cases. The post-Thanksgiving COVID-19 spike in the United States is now being felt in the weeks leading up to Christmas.

Many of those who travelled and held family gatherings for these holidays may have done so because they saw themselves as being at low risk for COVID-19 complications. They put their need for contact above contracting and spreading the virus. Such gatherings were potentially important for limiting some of the negative mental health effects related to weathering this pandemic. Indeed, half of all Canadians have reported worsening mental health since the onset of social distancing measures.

Individuals in high-risk groups are already more likely to be experiencing negative mental health effects brought on by protective measures. What might this mean as the holiday season continues to unfold?

In our recent study, we surveyed and interviewed Canadians with disabilities and chronic health conditions to see how they’re managing under COVID-19. We asked respondents a variety of questions about their backgrounds, their specific disabilities and health conditions, their concerns about COVID-19, their financial and employment situations, and their mental health during COVID-19.

Author provided

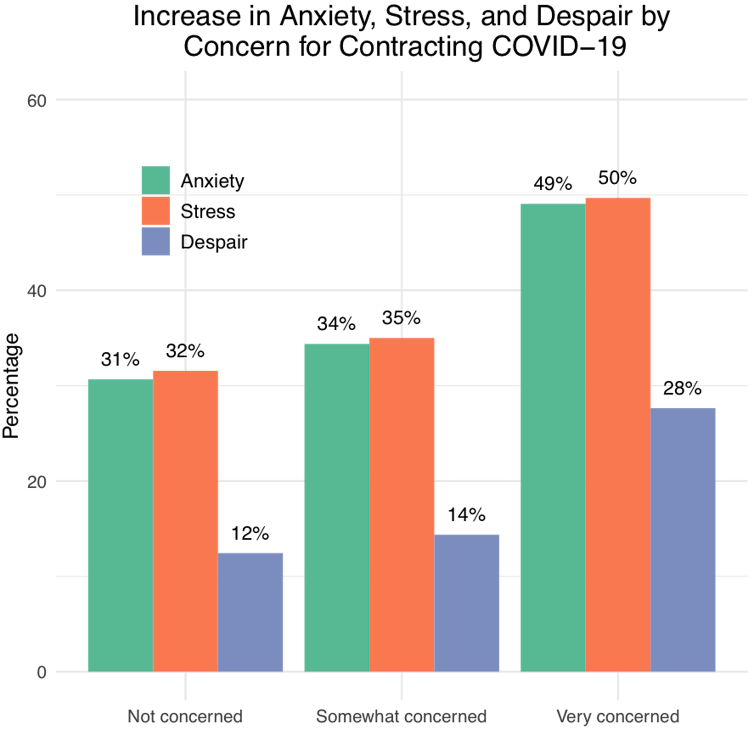

According to our survey conducted in June 2020 — collected when case counts were actually declining and provinces were beginning to open up and end their shutdowns — 78 per cent of respondents reported being concerned about contracting COVID-19. Heightened concerns were also associated with poorer mental health outcomes, as shown in the graph above. Among respondents who reported being very concerned about contracting COVID-19, 49 per cent reported increased anxiety, 50 per cent reported more stress and 28 per cent reported increases in despair.

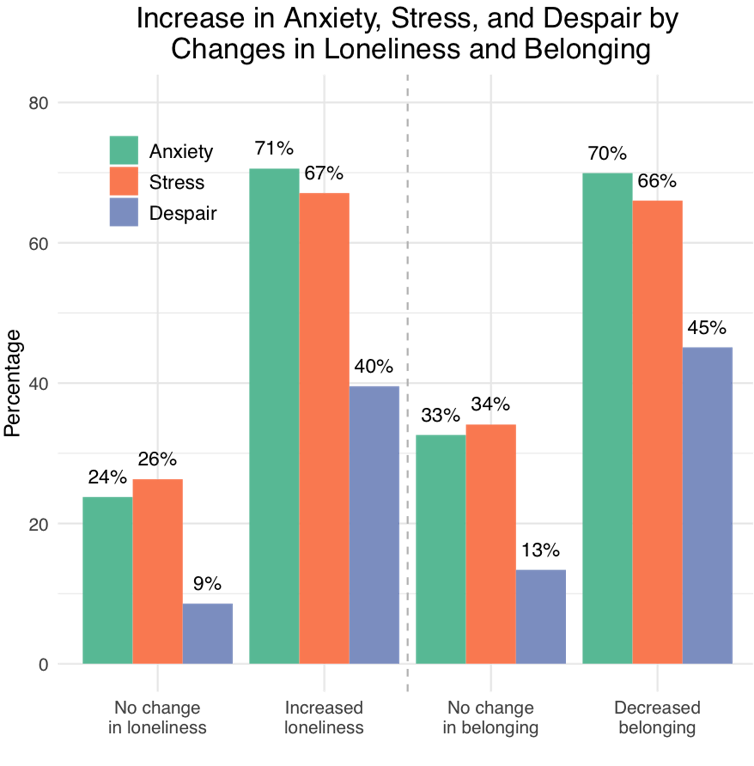

Respondents told us that they have been feeling lonelier during the pandemic and many also felt like their levels of belonging have declined. Thirty per cent reported increases in feelings of loneliness and 15 per cent reported decreases in feelings of belonging. Increases in loneliness and decreases in belonging were also correlated with negative mental health outcomes including increased stress, anxiety and despair, which is highlighted in the graph below.

Author provided

Our interview data, collected from August through October 2020, supports our survey findings. One respondent told us:

“Can’t go on dates, can’t meet up for friends, feel pretty lonely, feel pretty depressed. It’s pretty difficult. The only interaction I have is on Facebook and that gets me through the day for the most part, talking to people on Facebook. Other than that, not having a hug or any human interaction besides my parents, it’s kind of sad. It’s pretty depressing for the most part.”

Referring specifically to holidays, another respondent said:

“The beginning of the pandemic, the first two or three months were OK.… I don’t see loved ones nearly as much. We would have got together as a family for Easter and Thanksgiving. And I’m sure Christmas is also cancelled. So, I’m kind of feeling disenfranchised and not connected to anybody, anymore.”

Everyone is affected in one way or another by the virus and the measures taken to combat it. Many people are feeling the emotional and psychological toll of weathering this pandemic. It has been a long and hard journey through the storm and, even though we can now see the light at the end of the tunnel, the journey is not over yet.

However, we aren’t all feeling the effects of this journey equally. Many who already experience social barriers and poorer mental health status are especially vulnerable during a time when everywhere we look, we are reminded of a season associated with large gatherings of friends and family. Some we see often, others we only see during this time of year. Doing without these interactions over the holiday season will be hard for everyone. It’s important to remember that for some people, it is going to be especially hard.![]()

David Pettinicchio, Associate Professor, Sociology, University of Toronto and Michelle Maroto, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Alberta

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.